Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowAs the state of Indiana grapples with a significant shortage of attorneys, the Indiana Supreme Court is taking a new approach to tackle the issue.

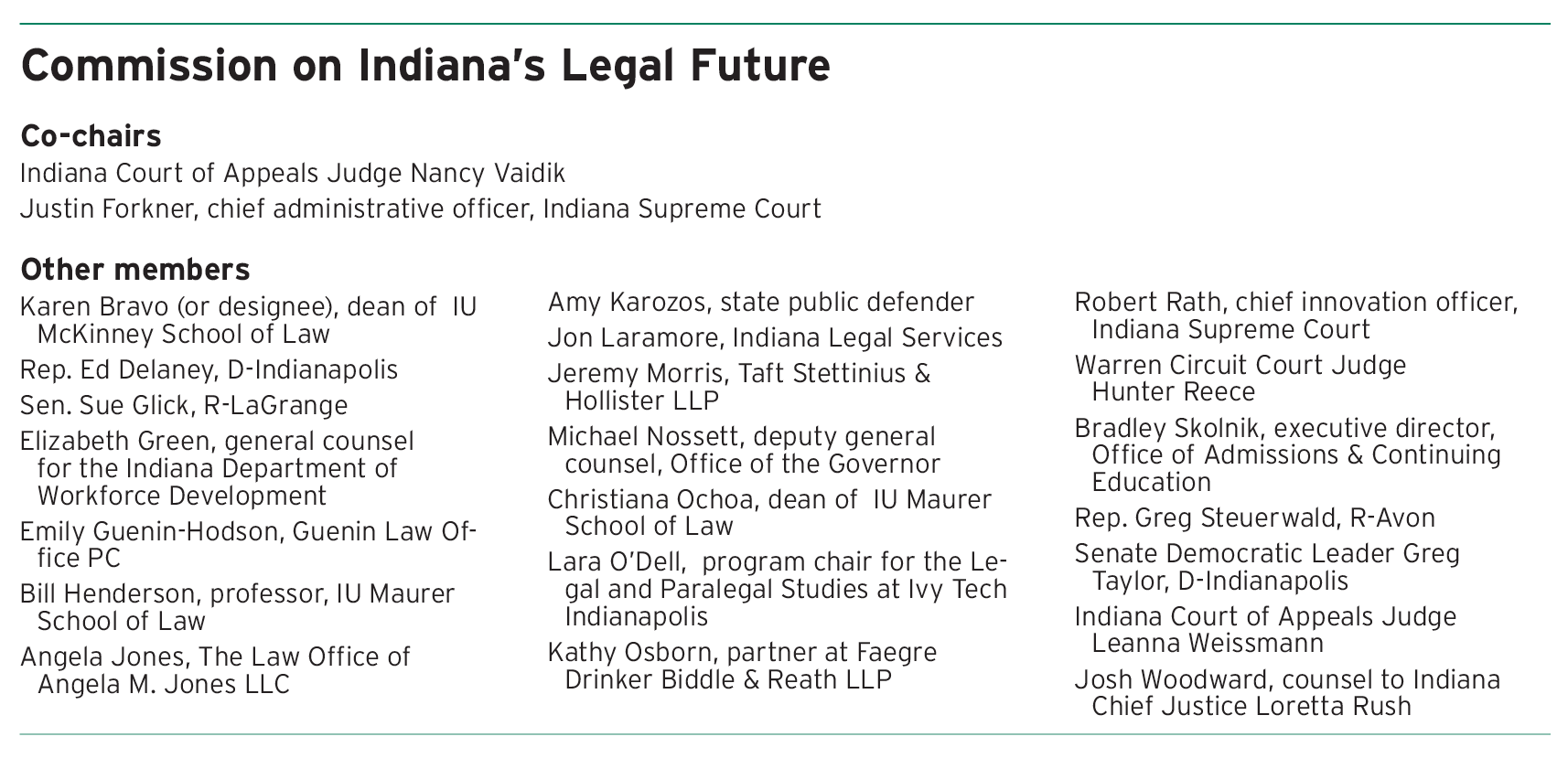

It has appointed a 23-member Commission on Indiana’s Legal Future to brainstorm just how to slow the decline and make Indiana a more appealing place to practice law through five focus topics: business and licensure models, pathways to admission & education, incentivizing rural practice, incentivizing public service work and technology applications.

Members of each subcommittee looking at those topics are professionals in the legal field who offer different perspectives.

Christiana Ochoa, a commission member and dean of the Indiana University Maurer School of Law in Bloomington, is grateful the Supreme Court is taking this step in combating the shortage.

“This is an all-hands-on-deck commission that is looking at it from a variety of perspectives all at the same time with a relatively short timeline so that we don’t lose time, so that we look for the lowest hanging fruit, and so that with so many people from different perspectives gathered around the issue, we can poke holes in the proposed solutions,” she said. “And that, I think, is exactly the approach we need.”

National outlook

But the Hoosier state is not alone in its growing need for legal representation, reflecting a greater problem across the United States.

The nation has not seen a significant boom in practicing lawyers since the 1970s, when the number of lawyers grew 76% for the decade, according to the American Bar Association’s 2023 Profile of the Legal Profession.

Growth in the 21st century slowed significantly, with an overall increase of 30%, or 1.3% each year, from 2000 to 2023, according to the ABA.

Right now, 39 states sit below the average number of lawyers per 1,000 residents in the United States, which is around 4. Indiana ranks 44th on the list, with 2.3 lawyers per 1,000 residents.

Indiana Senate Democratic Leader Greg Taylor of Indianapolis said solutions are ultimately about serving Indiana’s residents.

“I wouldn’t say there’s a specific number,” Taylor said, when asked if the commission has a specific “lawyer to resident” ratio they want to meet. “It’s really going to be basically, what can we do to make access to certain services more available to people?”

Across the country, states are taking different approaches to solving the shortage.

In Washington state, the Supreme Court in March approved alternatives to taking the bar exam for candidates to obtain their law license.The state’s Bar Licensure Task Force spent three years working on ideas before the court approved three experiential-learning alternatives, among other changes.

Since 2013, eligible attorneys in South Dakota receive an incentive repayment in exchange for five continuous years of practice in a rural county through the state’s Rural Attorney Recruitment Program. Each of these five payments equal 90% of one year of tuition and fees at the University of South Dakota School of Law.

And in Utah, the Supreme Court is testing out the legal regulatory sandbox (simply known as the “Sandbox”) to broaden access to legal services in underserved communities.

The pilot program, which runs through August 2027, allows law firms and other entities to use innovative legal services and business models that would otherwise not be offered under the state’s Rules of Professional Conduct.

One of the participating companies, Boundless Immigration, offers services for completing immigration documents.

How Hoosiers are addressing the issue

Before work began in the Commission on Indiana’s Legal Future, the Supreme Court and other professional organizations were already taking steps to bring more legal professionals to the state.

In February, the Indiana Supreme Court approved amendments to Admission and Discipline Rule 13 that will allow graduates of non-ABA-

accredited law schools to take the Indiana bar exam.

The court also will allow students who obtained their law degrees outside of the U.S. and received a graduate degree from an ABA-accredited law school in a program based on American law to take the state bar.

These changes take effect July 1.

Both Indiana University’s McKinney School of Law and Maurer School of Law are tackling the attorney shortage through the Rural Justice Initiative, which puts law students in rural counties to team up with judges or work as certified legal interns.

The program has been running since 2018.

Taylor, who is also a practicing attorney specializing in business transactions and public finance, is part of the commission’s subcommittee working to identify how the bar exam and methods of entrance into the legal profession can be improved to boost the number of attorneys in the state.

“I think our rules associated with admission to the bar is an important factor in determining if our rules are actually inhibiting attorneys from practicing in the state of Indiana,” Taylor said. “But it comes with a balancing act on making sure that we keep up the integrity of the bar in the state of Indiana.”

Members of the commission note that a significant number of Indiana counties are considered “legal deserts,” lacking the appropriate services to provide legal counsel to residents.

The Sandbox program in Utah is one method that commission member Kathy Osborn said her subcommittee is drawing inspiration from as they brainstorm how business and licensure models could be adjusted to combat the attorney shortage.

“Our group is looking at limited license paralegals or limited licensed professionals,” said Osborn, a partner with Faegre Drinker Biddle & Reath LLP. “Are there different kinds of certifications that we could provide to paralegals who have the right training to be able to represent those individuals without the oversight of a barred attorney?”

Though the committee is in the early stages of finding solutions, Osborn said she feels hopeful for the impact this commission can make.

“I am confident that the commission and the various work groups will come up with some good, creative ideas and hopefully get some things in place sooner rather than later to help,” she said.

The commission is expected to provide an interim report on recommendations by Aug. 1, should any of the proposed solutions need state funding through the Legislature, which reconvenes in January.

The commission is slated to issue a final written report by July 1, 2025.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.