Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowThe push for pay equity has taken a new shape in recent years, with a growing number of states taking steps to end pay disparities.

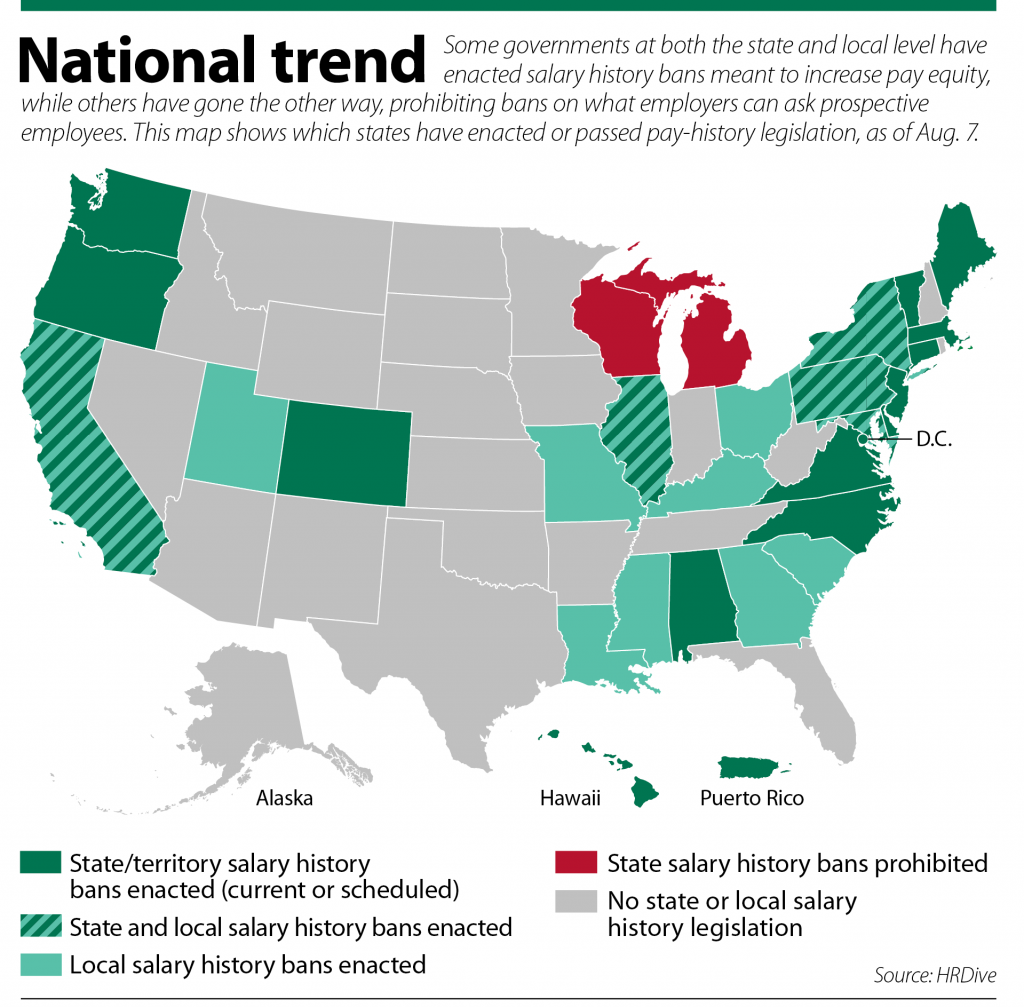

Using what’s known as “salary history bans,” governments at the state and local level are limiting employers’ ability to consider a candidate’s previous wages when making an employment decision. The breadth of these bans varies by jurisdiction, but the concept remains the same: under a salary history ban, an employer cannot explicitly ask a prospective employee what they earned in a previous job.

Employment lawyers say the popularity of salary history bans has grown in about the last five years. Some describe its growth as a “blue state” trend that has also extended to traditionally conservative states.

Indiana has not yet enacted a salary history ban at either the state or local level. But the conversation has begun in the Indiana General Assembly, and one lawmaker has already pledged to keep that conversation going.

“One thing that happens with salary history bans is, instead of looking at what a candidate was paid in the past, you focus on things like education — things that really are what you need to know,” Rep. Sue Errington, D-Muncie, said. “That’s what you’re looking for in an applicant, rather than, ‘Can I get a bargain?’”

Growing trend

Massachusetts set the stage for salary history bans, enacting a law in 2016 that took effect in 2018. Since then, states ranging from New York to Alabama have followed suit, alongside municipalities such as Philadelphia and Cleveland.

Each jurisdiction takes its own approach to a salary history ban, said Kathleen Anderson, a partner in Barnes & Thornburg’s Fort Wayne and Columbus, Ohio, offices. Some states prohibit an employer from asking a candidate about previous wages, while others go so far as to say that employment decisions cannot be based in any way on wage history.

In Alabama, an employer can ask a candidate about their previous wages, but the candidate has a right not to answer, according to a report from Littler Mendelson.

The initial Massachusetts law is more expansive, prohibiting employers from paying employees of one gender less than employees of another gender for comparable work, unless one of six factors are present, Littler reports. Those factors include a seniority system; a merit system; a system based on quantity or quality of production, sales or revenue; geography; education, training or experience; or travel. Salary history, however, is not a permissible reason for pay disparity.

The gender wage gap has long been a topic of conversation in American employment law. Erin Bauer of Barber & Bauer in Evansville gives the example of a male and female candidate interviewing for similar positions, where the male discloses a previous salary of $45,000 and the woman discloses a previous salary of $30,000.

If the employer is willing to hire both the man and woman, and if neither candidate is willing to take a salary reduction, then the employer will likely pay them both according to their previous salaries, Bauer said. Thus, the female candidate might get a raise to $35,000, but that is still less than the $45,000 the male was already making.

But women aren’t the only workers affected by the wage gap. Ryan Fox of Fox Williams & Sink in Indianapolis noted that minority workers also often encounter pay disparities.

“The idea is if potential employers are asking about what candidates made in their last job and then base their pay on what the employee earned before, they are, perhaps unintentionally, continuing that disparity,” Bauer said.

A split

Even with salary history bans in place, employers still need to know what candidates expect for compensation. To that end, Anderson said states that have instituted bans still allow salary-related questions.

Usually, Anderson said, that question is something along the lines of, “What are your salary expectations?” Alternatively, employers can post the salary range in the job description.

“They don’t want to be recruiting someone all the way through, only to find out that person wouldn’t take the job for the amount at issue,” Anderson said.

But as salary history bans have become more common, a circuit split has begun to form, Fox said.

The 9th Circuit has been favorable to the bans, handing down Rizo v. Yovino, 887 F.3d. 453 (en banc), in 2018. The Rizo decision held that “prior salary alone or in combination with other factors cannot justify a wage differential,” because relying on prior salary could allow employers to “capitalize on the persistence of the wage gap and perpetuate that gap ad infinitum.”

But Fox pointed to a recent Illinois decision that shows a different reasoning in the 7th Circuit.

In Hubers v. Gannett Co., a March 2019 decision out of the Northern District of Illinois, the judge relied on 7th Circuit precedent in ruling for employer Gannett Co. in a gender wage discrimination suit. That precedent — Wernsing v. Department of Human Services, 427 F.3d. 466, 468 (7th Cir. 2005), and Lauderdale v. Illinois Department of Human Services, 876 F.3d at 908 (7th Cir. 2017) — holds that “prior wages are a valid ‘factor other than sex’ justifying a pay disparity.”

“The undisputed evidence shows that Martin’s base salary was higher than Hubers’s, not because of sex, but because of his prior salary … ,” the Illinois court held. “Accordingly, Gannett is entitled to summary judgment as to Hubers’s claims of disparate pay premised upon the Illinois and Federal Equal Pay Acts.”

This split can be resolved in one of two ways, Fox said: state legislation or Supreme Court action. Rizo was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, but the justices denied the certiorari petition last month.

Coming to Indiana?

Jurisdictions in each of Indiana’s neighboring states have enacted legislation related to pay history bans. Illinois has implemented a statewide ban after Chicago passed a city ban, while municipalities in Ohio (Cincinnati and Toledo) and Kentucky (Louisville) have enacted local prohibitions.

Jurisdictions in each of Indiana’s neighboring states have enacted legislation related to pay history bans. Illinois has implemented a statewide ban after Chicago passed a city ban, while municipalities in Ohio (Cincinnati and Toledo) and Kentucky (Louisville) have enacted local prohibitions.

Michigan, however, has gone the opposite direction, actually prohibiting salary bans in favor of allowing employers to ask about previous wages. Wisconsin has also prohibited salary bans, Fox said.

Rep. Errington has introduced salary ban legislation in the Indiana General Assembly twice, in 2019 and 2020. Her original bill in 2019 was more expansive, she said, but her 2020 legislation was narrowly tailored to only prohibiting questions about previous wages.

House Bill 1162 did not get a hearing this year in the Committee on Employment, Labor and Pensions, a fact Errington said is partially attributable to the short 2020 session. Given other pressing legislation, Errington said her salary history bill was not a priority.

But the lawmaker said she will reintroduce the legislation. She plans to file a narrow bill, similar to what she presented in 2020, in the coming 2021 session.

Pointing to a recent study from Boston University, Errington said salary history bans have proven effective in narrowing the wage gap. That study, released in June, found that with the bans in place, women saw an 8% increase in pay, while Black workers saw a 13% increase.

Though employers can find it difficult to navigate the differing laws state by state, lawyers say achieving pay equity is a goal shared by many.

“I don’t know any employer who isn’t committed to pay equity in their approach to recruitment,” Anderson said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.