Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowEvery fall, judicial representatives from several Indiana counties travel to the Statehouse to make the same plea: Our caseloads are growing and our litigants are waiting, the judges tell lawmakers. We need more help, and we need your permission to get it.

Sometimes, growing caseloads are attributed to the opioid crisis. Sometimes, it’s an ever-expanding number of children in need of services cases. And sometimes, simple population growth can make a county’s docket busier. Or maybe it’s all three.

Regardless of the reasons, counties in need of additional judicial resources can’t simply ask for help. They must garner local support, then take their case to the Legislature, which has the final say on which counties get an extra magistrate or court.

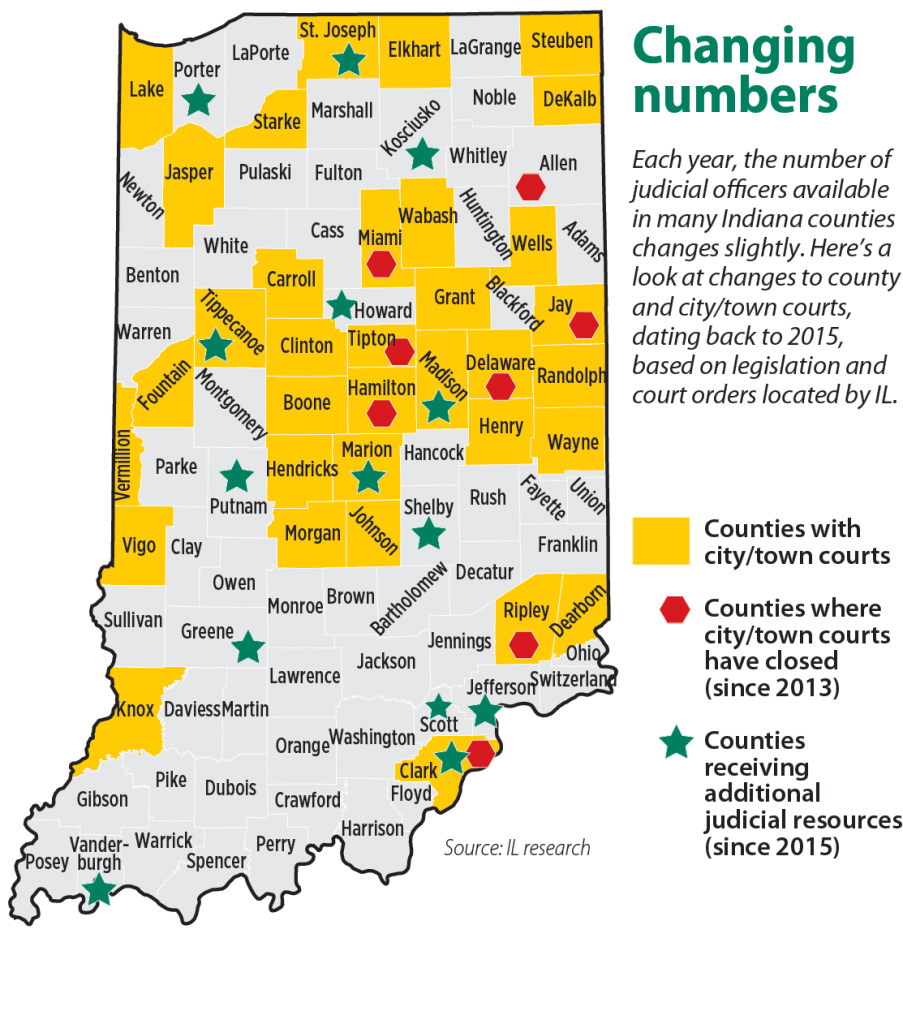

This year, the General Assembly signed off on additional resources for courts in three counties: Howard, Tippecanoe and Vanderburgh. Clark County also sought two additional courts during the 2019 General Assembly, but an amendment stalled the bill.

Though weighted caseload numbers from the Indiana Supreme Court show each of those counties are short multiple judicial officers, the numbers are not enough — judges must go through a set process to secure an extra judge.

Here’s a step-by-step look at how the process works.

Step 1: Local support

Before a request for additional magistrates or courts get to Indianapolis, judicial officials must seek support from their local lawmakers, all the way down to the county level. In Tippecanoe County, for example — which was allocated an additional superior court — Judge Randy Williams said county officials began working on plans for the new court two years before taking the request to the Statehouse in Indianapolis.

At that time, Williams, who led the effort for a new superior court in Tippecanoe County, said judges were struggling under the weight of growing caseloads. The population of the county had grown by about 40,000 people since the last time a new court was created, he said, and the opioid epidemic was creating more litigation. Plus, students at Purdue University often find themselves in trouble for low-level offenses.

Around the same time, the county commissioners had begun toying with the idea of renovating the local courthouse. That would be necessary to house a new court, Williams said.

Williams then began the process of obtaining official support from the county commissioners, as well as from stakeholders in the judicial system. He also presented the case for a new court to Tippecanoe County’s elected state lawmakers.

The situation was slightly different in Vanderburgh County, where Judge Wayne Trockman concedes that what his county really needs is a whole new court, not just the two new magistrates it received this year. Though the magistrates are effective in helping to move the docket along, they don’t come with their own staff — particularly bailiffs or court reporters — so they cannot function as independently as judges can.

But Vanderburgh County wasn’t in a place where it was able to pay for an entirely new court, Trockman said, particularly the costs of making space for a new judge and staff in the courthouse. So instead, the local judges opted for the help they could get support for — a new magistrate each for superior and circuit court.

Step 2: Summer study committee

If local support for a new magistrate or court can be obtained, county officials must then make their case to the Interim Study Committee on Courts and the Judiciary. According to Rep. Wendy McNamara, the Evansville Republican who helped local judges create the Vanderburgh County magistrates bills, a request for additional judicial resources that doesn’t receive the support of the interim committee in the fall won’t be considered by the full General Assembly in the winter.

This process was created to curb instances of what were viewed as abuses of the system, McNamara said. The Evansville Republican has heard stories of a county receiving additional judges based on its purported need, but lawmakers later finding out the need for that particular county was not really there.

That’s where the concept of the weighted caseload report came in, McNamara said. The Indiana Supreme Court now tracks counties’ needs based on the number of judges they actually have, the number of judges they need and the judges’ utilization.

The court describes utilization as “the number of cases filed and the number of judicial officers available to hear them.” Statewide, the average utilization is 1.05, according to the court’s website. That means that on average, each judge carries a caseload that should actually be carried by 1.05 judges – 5 percent more than the desired standard.

In Tippecanoe County, Williams said the county’s busiest superior court was working at 230 percent of the recommended standard in 2018. The “least busy” superior court was working at 136 percent.

Those numbers help lawmakers get a realistic sense of each county’s judicial needs when they present their requests, McNamara said. But even if a county has a demonstrated need for an extra judge, the legislation could fall through at the study committee level if the local support isn’t there.

“If local officials can’t agree, there’s no reason for the Legislature to get involved in the middle of a local fight,” McNamara said.

Step 3: General Assembly

The final stop on the journey to extra judicial resources is the full General Assembly. House bills start in the Courts and Criminal Code Committee, chaired by McNamara, while Senate bills start in the Judiciary Committee.

Clark County’s ask for two new circuit courts sailed through both the House and Senate without opposition. The county’s courts have long been known as among the busiest in the state, and local officials had put together a plan for housing the new judges and their staffs, said Rep. Terry Goodin, D-Austin, who authored the House bill.

But the measure stalled after getting out of the Senate, when it returned to the House with an amendment that would have initially appointed the new judges, then held the first election in 2024.

“That’s almost a full term,” Goodin said. “I just felt like the judges should’ve been elected.”

Goodin said Clark County officials were disappointed at the turn their bill took, noting that it seemed like “Indianapolis” felt it knew better than the local government. But he’s already been asked to sponsor a similar bill next year, so he expects the legislation to be revived.

The disappointment, Goodin said, stems from the fact that Clark County’s growing caseload is taking the “speedy” part out of a fair and speedy trial. Trockman expressed similar concerns about the Vanderburgh County docket, noting that in family law cases, litigants were waiting three to four months to get a contested hearing date.

But the county’s new superior court magistrate is already helping the docket move more quickly, Trockman said. Even so, the local judges are still planning to begin working with county officials to make the necessary space for a new judge with staff.

In Tippecanoe County, Williams said the new superior court judge will be elected in 2020 and will begin work in 2021.

Judge Douglas Tate of Howard Superior Court III did not respond to a request for comment about the new magistrate jointly allocated to the Howard circuit and superior courts. Vicki Carmichael, chief judge of the Clark County courts, also did not respond to a request for comment.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.