Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowWith the implementation of Criminal Rule 26 in January, courts across Indiana have been required to begin using evidence-based practices to make pretrial release decisions. But do those practices actually improve the criminal justice system?

Up to this point, there’s been little evidence to determine whether pretrial risk assessment tools are effective. But a recent series of studies has looked to Indiana to begin answering that question.

One study of five counties — Allen, Hamilton, Hendricks, Jefferson and Monroe — found “good-to-excellent” performance of the IRAS-PAT, or Indiana Risk Assessment System-Pretrial Assessment Tool. The IRAS-PAT is a seven-factor analysis used in many Hoosier courts to aid in pretrial release decisions.

Another study of four counties — the same counties, minus Jefferson — showed that the use of assessments in pretrial release decisions was associated with slightly higher rates of re-arrest, mostly for nonviolent new offenses. That means that more defendants could secure pretrial release using assessment tools, but the rate of a pretrial re-arrest might go up.

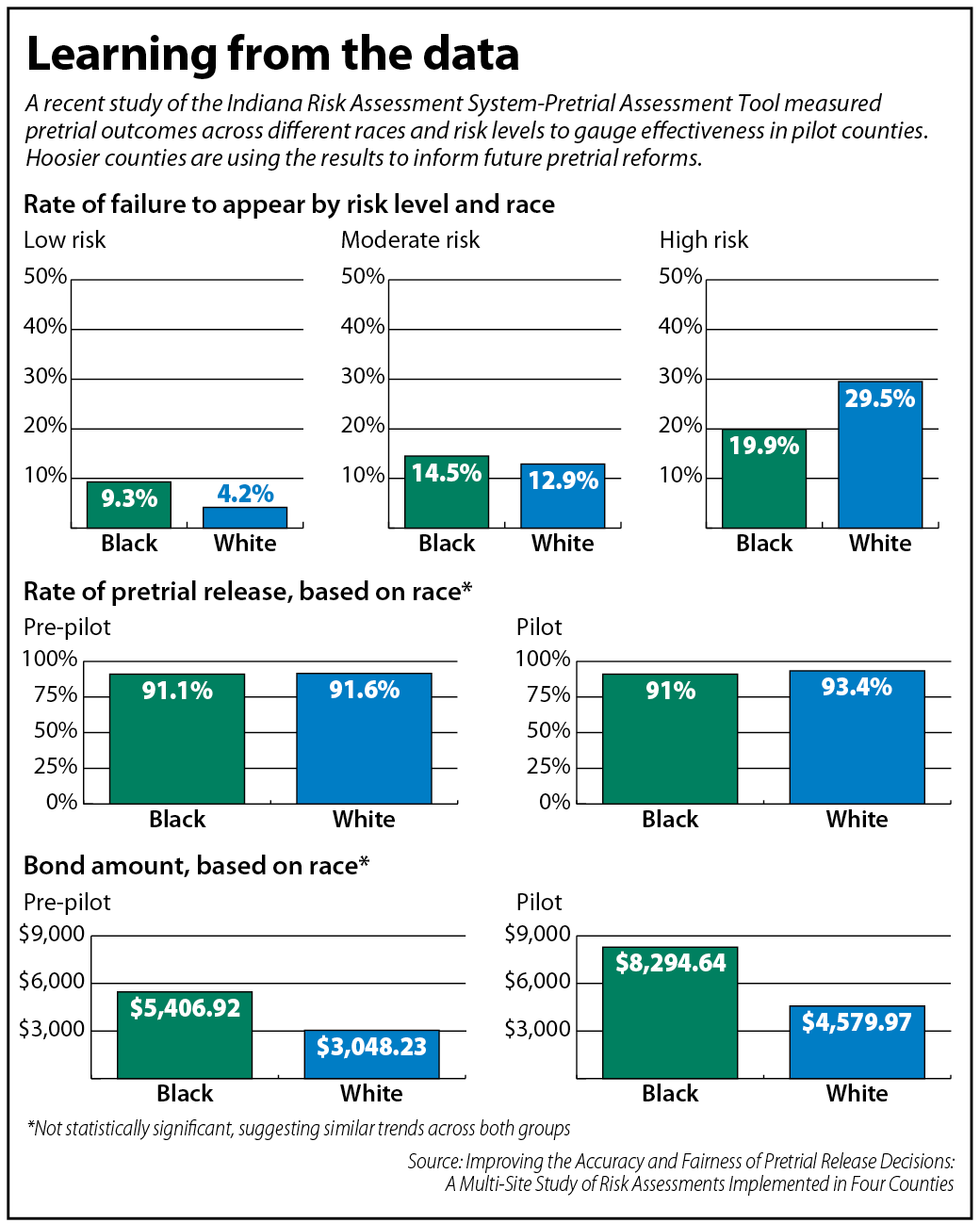

Notably, the four-county study found no evidence of disparate treatment between Black and white offenders. However, the study also did not find a reduction in pretrial disparities.

All of this research leads to one conclusion: more research needs to be done. But even with many questions still unanswered, pretrial reform advocates say they plan to use what data is available to further refine their pretrial programs.

Crunching the numbers

The four-county study — “Improving the Accuracy and Fairness of Pretrial Release Decisions: A Multi-Site Study of Risk Assessments Implemented in Four Counties” — was led by Evan Marie Lowder, a professor at George Mason University who worked with scholars at the Indiana University O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs and Wayne State University. Lowder said Indiana’s IRAS-PAT is showing itself to have the same predictive validity as similar tools used in other jurisdictions.

In other words, Lowder said the IRAS-PAT is as accurate as other tools at predicting a defendant’s risk of a pretrial offense. Low-risk defendants generally have the lowest levels of offenses, while the reverse is generally true for high-risk defendants.

Put numerically, Lowder gave a zero to one scale, with one indicating perfect prediction. The five-county study scored Indiana at a 0.67 for new criminal activity on pretrial release and 0.71 for failures to appear. A “good score,” she said, falls in the 0.64 to 0.70 range, while an excellent score sits at 0.71 and above.

In practice, those numbers bear out, county officials say. Failures to appear have been falling, with Monroe County reporting a 92.6% appearance rate from Oct. 1, 2016-Sept. 30, 2019. Hamilton County has seen similar results, recording an FTA rate of 6.7% in 2019, compared to about 9% in 2016.

Pilot programs

Those improvements are the result of nearly four years of practice, county officials say.

In Monroe County, deputy chief probation officer Troy Hatfield leads the county’s pretrial reform efforts and participates in statewide pretrial reform work. Part of the process in his county, Hatfield said, was determining the right population to receive pretrial risk assessments.

Ultimately, that population turned out to be everyone. Pretrial detainees and defendants who have bonded out are assessed, and those assessments are provided to the court. The only population carved out are those who are newly arrested while on probation and community corrections.

Another key piece of the Monroe County program has been determining how to respond when a defendant who is released pretrial violates the terms of their release, such as through failure to appear or a failed drug test. The strategy so far, Hatfield said, has been to deal with those violations administratively, rather than filing for a court warrant, unless there is a threat to public safety.

In Hamilton County, pretrial assessment has always included all new arrests at all levels of offenses, said Stephanie Ruggles, director of Hamilton County pretrial services. The county has since started to also assess suspects who are arrested pursuant to a warrant.

In Hamilton County, pretrial assessment has always included all new arrests at all levels of offenses, said Stephanie Ruggles, director of Hamilton County pretrial services. The county has since started to also assess suspects who are arrested pursuant to a warrant.

For more serious violations, such as a new felony arrest, Ruggles said Hamilton County will file a violation with the court, which could lead to the revocation of supervised release in favor of a bond. But smaller technical violations such as FTAs will be worked out with the defendant to the extent possible, similar to Monroe County.

“We try our best not to file technical violations quickly, but try to do everything we can to get ahold of them and find out what is preventing them from coming in,” she said.

Dissent

Both Hatfield and Ruggles are enthusiastic about the research partnerships with Lowder, believing that having more data leads to better outcomes for the criminal justice system as a whole. Many states have adopted tools similar to the IRAS-PAT, but a leading pretrial reform group has renounced its support of those tools.

According to Meghan Guevarra, an executive partner at the Pretrial Justice Institute, the information collected through assessment tools is inherently biased. Black men are likelier to be arrested and rearrested, she said, and that societal discrimination is built into risk assessments.

What’s more, Guevarra said, assessment tools are often misused. The tools are meant to inform the conditions of release, but they instead are sometimes used to determine detention versus release or the setting of money bond.

“For all those reasons put together, we can’t support the use of assessments anymore,” Guevarra said. “We still don’t support the use of monetary bond either.”

Instead, PJI urges states to follow the language of their constitutions. If those constitutions don’t allow for legal pretrial detention, then everybody should be released pretrial. But, she added, “that’s not something we’ve seen much.”

Further study

Lowder acknowledges that some risk assessment factors reflect “very real, deep-seated systemic racism in our society.” The predictive validity can also be less accurate with respect to ethnic and racial minorities, she added. But what she does not agree with is the notion that using that data deepens existing disparities.

“One of the first things you learn as a social scientist is that very few trends can be observed in a vacuum. Rather, any sort of trend always begs a comparison,” she said. “If you want to know whether risk assessments will deepen racial disparities, then you have to compare it to something. And likely what you’ll be comparing it to is a system that has already shown evidence of pervasive inequalities.”

A next step for Lowder is to do a deeper study of predictive validity based on race. Additionally, she’s working on a five-county study on the effectiveness of supervision strategies, focusing on Bartholomew, Hamilton, Hendricks, Jefferson and Monroe counties.

In Monroe County specifically, Hatfield plans to begin analyzing the collection and use of pretrial fees for services such as electronic monitoring. He’d also like to launch an immediate jail assessment program, though that program is currently hindered by staffing issues.

For Hamilton County, Ruggles hopes to expand the assessments of warrant arrests. She’s also eagerly awaiting the results of Lowder’s supervision study, because, she said, “the last thing we want to do is to over-supervise someone who hasn’t been convicted.”

Statewide review

On the state level, Grant Circuit Judge Mark Spitzer leads the Indiana Pretrial Committee. With the new data in hand, the committee is preparing to review the results and adjusted Indiana’s pretrial standards accordingly.

Additionally, the committee hopes to soon grant pretrial certification to all pilot counties, Spitzer said. The pretrial certification program is modeled off of the problem-solving courts, though the certification process has slowed as the COVID-19 pandemic curbed site visits.

Notably, the evidence-based decision-making team has been moved under the umbrella of the Justice Reinvestment Advisory Council. According to Spitzer, that will lead to structural changes in how pretrial reform efforts are reviewed on a statewide level.

But “the committee continues to meet remotely,” Spitzer said. “We’re continuing to do our work, and not letting the pandemic prevent us from analyzing the data and tweaking our pretrial rules.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.