Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowDoes a gratuity given to a public official after a city contract is awarded constitute a crime?

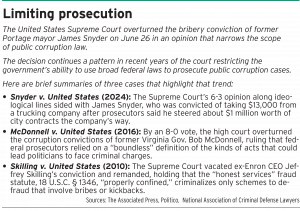

In James Snyder’s case, the U.S. Supreme Court said no. The high court overturned the bribery conviction of the former Portage mayor in June, issuing a 6-3 opinion in favor of Snyder, who was convicted of taking $13,000 from a trucking company after prosecutors said he steered about $1 million worth of city contracts the company’s way.

Legal observers took a special interest in Snyder’s case and the court’s opinion because of its potential impact on federal anticorruption law and its reversal of the body law regarding gratuities.

Jackie Bennett, a Taft Stettinius & Hollister LLP partner in the firm’s Indianapolis office, was one of three Taft attorneys who represented Snyder. He pointed out that in 1984, Congress passed 18 U. S. C. §666 that extended a gratuities prohibition to most state and local officials. Congress amended §666 to avoid the law’s “possible application to acceptable commercial and business practices.”

The federal criminal code prohibits bribery for federal officials and state officials in separate provisions.

Bennett said the high court correctly decided that the statute applies solely to bribery, not gratuities.

“I think there was a recognition that there was something of an ambiguity in the statute,” Bennett said of the court’s ruling in Snyder’s case.

Steve Sanders, an Indiana University Maurer School of Law professor, said the ruling represents a categorical change in federal law and arguably makes it safer to accept a gratuity.

Sanders said the Snyder decision clearly makes a change in anticorruption law.

“It unquestionably does weaken federal public corruption law,” Sanders said.

Kavanaugh writes for the majority, Jackson dissents

In Snyder’s case, the city put out a public bid for modernized garbage trucks, and a local vendor won.

After the vendor won, a check was written to Snyder for $13,000. Snyder and the vendor maintained that the check was not connected to the trucks, and instead was a consulting agreement the parties reached after the bids were complete. Federal prosecutors, however, maintained that the check was a “reward” under section 666, or an after-the-fact gratuity.

Bennett, a trial attorney and former federal prosecutor, said there wasn’t any payment tied to the contracts.

“There was never any proof the payment was in connection for the official act,” Bennett said.

He said Snyder just wanted to automate the city’s garbage collection process, which the Taft attorney said ending up saving the city millions of dollars.

Snyder’s attorneys argued before the high court that prosecutors hadn’t proved there was a “quid pro quo” exchange agreement before the contracts were awarded and that prosecuting officials for gratuities given after the fact unfairly criminalizes normal gift giving, according to the Associated Press.

The Justice Department countered that the law was clearly meant to cover gifts “corruptly” given to public officials as rewards for favored treatment.

But Justice Brett Kavanaugh, writing for the conservative majority, said “the government’s interpretation of the statue would create traps for unwary state and local officials.”

A gratuity or reward could be unethical or illegal under other laws, but it doesn’t violate the law Snyder was charged with breaking, he said.

In a sharply worded dissent joined by her liberal colleagues, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson said that that reading ignores the plain text of the law. She said Snyder’s argument was an “absurd” reading of the law that “only today’s court could love.”

Eric Petry, counsel in the Brennan Center for Justice’s Elections and Government Program, said he is very concerned with the court’s decision, describing it as an example of the court’s conservative supermajority paring back anticorruption law.

Petry said the court’s opinion is rooted more in ideology than any legal rationale and, as Jackson noted in her dissent, flies in the face of the plain text of the statute.

“It bodes poorly for the future of anticorruption law,” Petry said of the decision, which he called “shocking.”

How will opinion impact public corruption law?

Snyder was elected mayor of the small Indiana city of Portage, located near Lake Michigan, in 2011 and was reelected four years later.

He was indicted and removed from office when he was first convicted in 2019.

Bennett said Snyder was ecstatic about the Supreme Court decision. He noted that the investigation into the former Portage mayor began in 2012, with his first trial taking place in 2019.

“This thing has been hanging over his head,” Bennett said.

Indiana Lawyer attempted to reach Snyder by phone, but was unsuccessful.

Some court observers viewed the opinion as similar to the one issued by the Supreme Court when justices overturned the bribery conviction of former Virginia Gov. Bob McDonnell in 2016.

Petry said he thought it would be a real mistake to lump the Snyder decision in with McDonnell’s and others linked to public corruption law.

He said in McDonnell and other similar cases, there was a real concern about due process and prosecutorial overreach.

Petry noted that conservative and liberal justices agreed in those cases that, however distasteful their conduct, the defendants in these cases could not reasonably have known their behavior would land them in federal prison because it did not clearly fall within the plain scope of the laws at issue.

By contrast, Petry argued that Snyder accepting kickbacks for the garbage contract goes to the heart of the federal anticorruption statute.

“It’s hard for people to have confidence that the court will hold up these statutes,” Petry said.

Sanders added that he wasn’t surprised the high court took the Snyder case.

He compared the court’s decision to the one it made in June for one involving the prosecution of a former police officer involved in the Jan. 6, 2021, U.S. Capitol riot. In that case, the justices ruled 6-3 to throw out a lower court’s decision that had allowed a charge of corruptly obstructing an official proceeding.

Sanders said this Supreme Court seems to interpret laws more narrowly and literally than in the past.

Sanders said this Supreme Court seems to interpret laws more narrowly and literally than in the past.

“This is not a court that’s bashful in reigning in federal prosecutors,” Sanders said, adding that federal prosecutors are accustomed to using laws aggressively.

To counter the Snyder decision, Congress could always step in and change the law, Sanders said. He acknowledged that was not likely with the current congressional dysfunction.

Bennett said the Snyder decision could result in other people convicted on similar charges to seek expungements. He cited ex-Illinois House Speaker Michael Madigan bribery case as one example.

WTTW in Chicago reported attorneys representing four former Commonwealth Edison officials will formally ask a judge to toss out their clients’ convictions, more than a year after they were found guilty of conspiring to bribe Madigan.

The Chicago Sun-Times reported that prosecutors and defense attorneys in Madigan’s case told a judge they hope to keep his trial on track for October, despite the Snyder ruling.

They also told U.S. District Judge John Blakey that the feds have no plan to file a revised indictment against Madigan in the wake of the high court decision.

Madigan’s trial was scheduled to start in April but was postponed until the Snyder case was resolved.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.