Subscriber Benefit

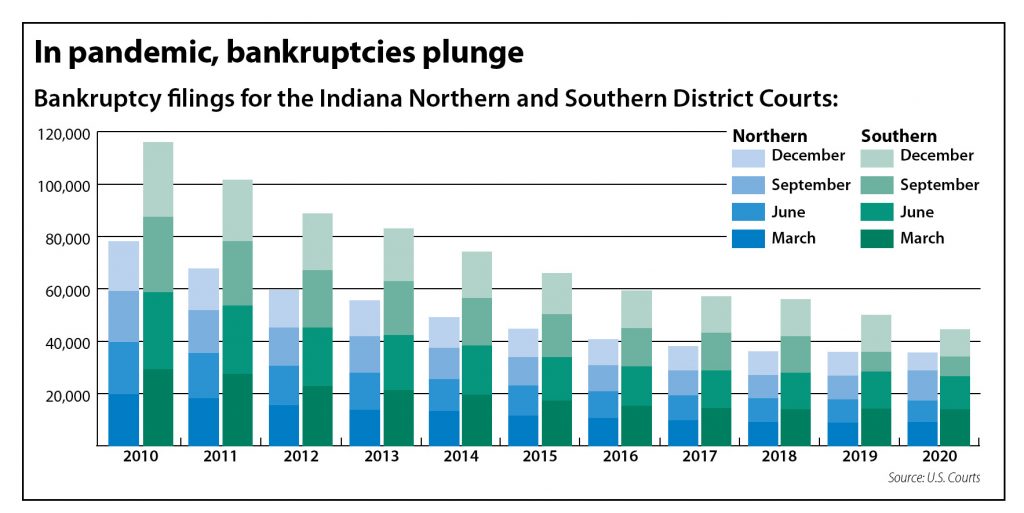

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowEconomists thought economic turmoil caused by the COVID-19 pandemic would cause bankruptcy filings to surge. Instead, they’ve plummeted, which is forcing bankruptcy practitioners across the state to cut costs or find other work to fill the void.

“The reduced numbers have been a shock. Everybody’s numbers are down, and there’s not much you can do about it,” said Mark Telloyan, an adjunct professor of law at Notre Dame Law School and partner at O’Brien & Telloyan.

In the 12 months ending March 31, 2021, bankruptcy filings tumbled 27.9% in Indiana and 38.1% nationally — a drop that occurred even as unemployment surged. The Indiana rate peaked at 17% last spring and has since declined to 3.9%.

Ball State University economist Mike Hicks said he can’t explain the disconnect.

“Other than the very large stimulus checks and extra $300 a week in pandemic unemployment, there’s little economic reason why bankruptcies would have fallen,” said Hicks, director of the university’s Center for Business and Economic Research.

“So, it’s either that or a non-economic reason, such as the pandemic causing families to postpone big decisionslike bankruptcy.”

What’s going on?

Hicks said part of the explanation is the dramatic change in American household consumption during the pandemic, including reduced travel, dining and entertainment expenses.

Debtors also have received wiggle room on many of their debts. For example, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a moratorium on evictions, and the federal government suspended requiring payments on student loans.

Banks also have been lenient with commercial clients, said John Allman of Hester Baker Krebs.

“In the last year, I think the lack of filings is truly a result of the banks and creditors not pushing. That’s what brings clients to us,” Allman said.

But Allman said he’s confident banks will get more aggressive. And other attorneys say consumers will feel additional pressure after the CDC eviction moratorium goes away next month, and the suspension on required student loan payments ends in September.

One in seven renters is behind on payments to their landlord, according to the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey. The average amount owed is $3,400.

Lean times

If his former colleague hadn’t retired at the beginning of the pandemic, Indianapolis bankruptcy attorney Jess Smith III said his firm, Tom Scott & Associates PC, would have had to significantly downsize in the ensuing months.

Even without his colleague, Smith had to turn back to his roots of general practice and take on other matters, such as divorces, adoptions and wills.

“What I have done is go back to the things I normally would have turned away or referred to others when we were just swamped with bankruptcies,” Smith said. “Normally we would refer those out but we have started handling those types of cases again at least until the bankruptcy filings pick back up.”

Even before the 2020 plunge in filings, bankruptcy attorneys already had felt the effects of fewer filings over the past decade. In 2010, in the aftermath of the 2008 Great Recession, cases nationally peaked at 1.6 million. By comparison, 2019 saw only 773,361 cases, according to the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts.

Then came the pandemic, which contributed to a 22% drop in Chapter 7 filings and 46% drop in Chapter 13 filings in 2020, compared with a year earlier, according to Epiq AACER. Chapter 11 commercial bankruptcies did rise 29% but make up a fraction of total cases.

Smith said his law firm was moderately impacted by the decline in filings. But it could have been much worse.

“We made the decision to close the third office when he retired. If we hadn’t, there would have been adverse impact of trying to staff the overhead of the three offices with the reduced volume (of cases),” he said.

“We made the decision to close the third office when he retired. If we hadn’t, there would have been adverse impact of trying to staff the overhead of the three offices with the reduced volume (of cases),” he said.

Telloyan, the Notre Dame adjunct professor, said 2021 is shaping up to be even worse.

“In 2020 we filed half of the cases we normally do. Our income stream has been dramatically reduced. It’s hard to keep everyone busy,” Telloyan said of his firm.

After the pandemic hit, the South Bend attorney said his practice moved from staffing two paralegals to one, with the remaining employee working fewer hours. With more time on his hands, Telloyan devoted more time to teaching.

Allman, who works primarily with commercial bankruptcy, said his law firm has felt the halt of new business coming in since last year.

“We have been fortunate that we have not had to (downsize), but I can appreciate that it’s going on out there. Particularly on the consumer side,” Allman said. “I think the consumer bankruptcies have dried up.”

Like others in the bankruptcy industry, Allman said he’s curious when filings will pick up.

“When is that going to change?” he said. “That’s what we are all asking.”

What’s to come?

Smith foresees a “gradual buildup” in cases, but not a surge.

“There will be a pent-up demand for bankruptcy services simply because of the depressed numbers in the last couple of years and last year and a half,” he said.

Bose McKinney & Evans attorney James Carlberg, who represents business clients, said the economic recovery could spare some struggling firms from having to file bankruptcy.

“The real question will be what happens later this year, if things are somewhat more normal. Then the question will be, how are the businesses performing and are they able to deal with the debt they have?” he said.

Longtime bankruptcy attorney Mike Norris said he isn’t too worried about the drop in bankruptcy filings after practicing for more than 40 years.

“It’s just ebb and flow and, frankly, our society is burdened with so much debt there will never be an end to bankruptcy filings or a permanent drop in them,” he said.

“I still expect a tsunami of filings by the end of 2022,” Telloyan opined. “Debt is a disease and we’ve got a lot of sick people.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.