Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowA ruling that was 15 years in the making has now sparked passionate discourse in the Indiana Statehouse as changes to wetlands occur.

In 2004, Michael and Chantell Sackett purchased a vacant lot in a residential subdivision near Priest Lake, Idaho. No surface water connection existed between their lot and the roadside ditch, or between their lot and Priest Lake.

Three years later, they begin construction of their family home. After they broke ground, officials from the Environmental Protection Agency and the United States Army Corps of Engineers informed the Sacketts’ construction crew that the lot likely contained wetlands subject to regulation under the Clean Water Act. They recommended all construction be put on hold until their compliance with the act could be established.

The EPA then found the Sacketts violated the act by trying to build their home without first obtaining a Clean Water Act permit. They were ordered to restore their property and were threatened with high administrative and civil penalties if they failed to comply.

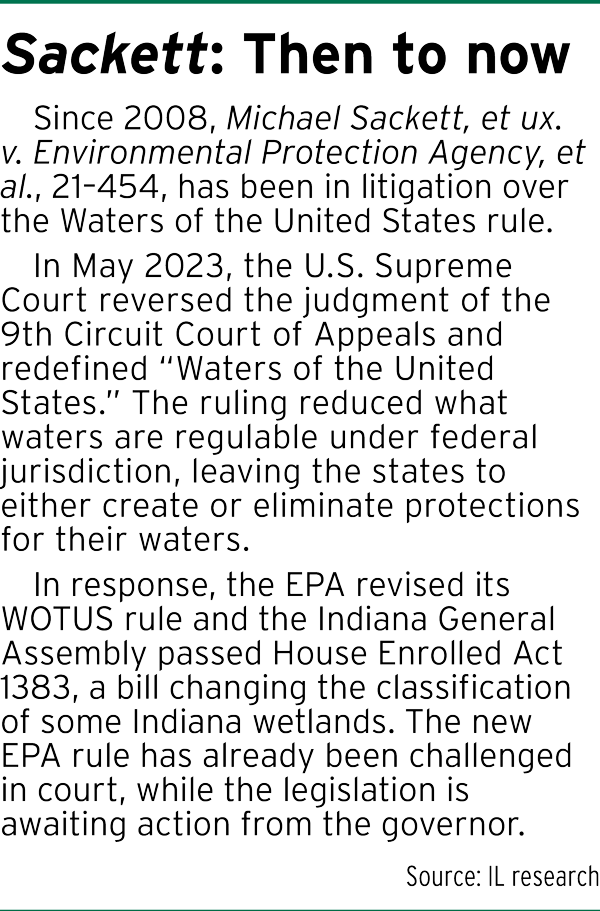

In 2008, the Sacketts requested an administrative hearing to contest the EPA’s determinations. The EPA denied the request, so action was taken before the U.S. District Court for the District Court of Idaho.

The district court ruled in the EPA’s favor, and the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed.

The district court ruled in the EPA’s favor, and the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed.

That took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, where, in 2012, the justices unanimously held that the Sacketts could challenge the EPA’s compliance order. The Sacketts and the EPA then spent years litigating at the district court over procedural issues.

In March 2019, the district court ruled that the EPA had authority to regulate the wetlands alleged to exist on the Sacketts’ lot.

The Sacketts again appealed to the 9th Circuit, and in 2021, the appellate court again affirmed the ruling of the district court.

The Sacketts then returned to the U.S. Supreme Court, which was tasked with deciding the proper test for wetlands jurisdiction under the act, and whether their lot was regulable.

In May 2023, the court reversed the 9th Circuit’s ruling.

“In sum, we hold that the CWA extends to only those ‘wetlands with a continuous surface connection to bodies that are ‘waters of the United States’ in their own right,’ so that they are ‘indistinguishable’ from those waters,” Justice Samuel Alito wrote for the court. “This holding compels reversal here. The wetlands on the Sacketts’ property are distinguishable from any possibly covered waters.”

Clarity or confusion?

Damien Schiff, a senior attorney with the Pacific Legal Foundation, which litigated the case on the Sacketts’ behalf, said the ruling is important mainly because it eliminated uncertainty that surrounded the act for decades.

“It did so by both definitively rejecting what was EPA and the Corps’ preferred standard for wetlands jurisdiction — the so-called ‘significant nexus test’ — and replacing it with what we think is a much clearer and much more readily administrable test, which derives from Justice (Antonin) Scalia’s plurality opinion in Rapanos, which you could call the ‘continuous service connection test,’ but I think it’s been referred to as the ‘indistinguishability test,’” Schiff said, referencing Rapanos v. United States, 547 U.S. 715 (2006).

After litigating the case for 15 years, Schiff said it’s not just a victory for the Sacketts.

“I think it’s a great win for the Sacketts, but a great win for property owners throughout the country,” he said. “It’s a test that’s much easier to administer. It’s one that the lower courts will be able to employ, I would hope, without much controversy now.”

In response to Sackett, the EPA amended its definition of “Waters of the United States,” with the new rule taking effect in September 2023.

Now, nearly a year after Sackett came down, Schiff said a few states have filed litigation against the new rule, including Texas and North Dakota.

There has also been pushback against the SCOTUS ruling from the EPA and the Corps, Schiff said, although from his perspective, there are no remaining questions.

“It’s really quite clear, at least as it comes to, what’s a regulable water under the Clean Water Act?” he said. “And when a wetland can be regulated, the tests are pretty straightforward, and so there shouldn’t be much left to decide.”

Indiana debate

One effect of Sackett has been to leave it more to the states to decide whether to increase or decrease wetlands protections.

In Indiana, that debate has played out in the Legislature via this year’s House Enrolled Act 1383 — the first bill to reach the governor’s desk.

HEA 1383 reduces wetlands protections by shifting some Class III wetlands — which are currently protected — down to Class II, which have far fewer safeguards, according to the Indiana Capital Chronicle.

Although it advanced through the General Assembly quickly, debate surrounding HEA 1383 was robust.

Indra Frank, director of environmental health and water policy at the Hoosier Environmental Council, noted Class II wetlands are already subject to several exemptions.

Those exemptions came through 2021’s Senate Enrolled Act 389, which changed the definition of Class II wetlands and provided exemptions for what activity can occur without a permit.

“In July of 2023, I requested the wetland permitting data from the state agency to see what impact Senate Bill 389 had had, and what the data show is that following Senate Enrolled Act 389, only 25% of the wetland acres being impacted in in Indiana are getting mitigation,” Frank said. Mitigation occurs when a replacement wetland is built to make up for the lost function of the wetland that was impacted.

“That means 75% of the wetland acres being lost are being lost with no mitigation of their loss function,” Frank said.

David Van Gilder, senior policy and legal director at HEC, added that people get frustrated when it comes to understanding the scientific issue of what is and isn’t a wetland.

“In my view, the frustration expressed by the folks who support the builders and developers is that they just they don’t see any value in lands that are, would be characterized as wetlands — they don’t see any dollars and cents there,” Van Gilder said. “Unfortunately, scientists and people who are involved in all of this know that that’s foolish.”

He gave the example of a 30-acre wetland upstream of a small town that has a storage capacity of 30 million gallons of water. If that is destroyed, Van Gilder said, then that water could flow downstream and flood the town.

“I can assure you that storm water managers would be able to put a dollar figure on that,” Van Gilder said.

But Sen. Rick Niemeyer, R-Lowell, who sponsored the bill in the Senate, said there has, in fact, been a focus on mitigation in consultation with the Indiana Department of Environmental Management.

“I don’t think it will take away a lot of wetlands,” Niemeyer said during a final debate on the Senate floor. “It might change some classifications in the state of Indiana that need to be changed — they don’t meet the qualifications in the level they’re in now.”

Sen. Shelli Yoder, D-Bloomington, was an outspoken opponent of HEA 1383. She criticized Republican leaders for “rushing” the bill, although supporters maintain that all proper processes were followed.

“The fact that this harmful, costly, anti-conservation policy has being rushed through session — clear from the fact that it passed out of the Senate before we’ve even reached the official mid-point of session — speaks volumes,” Yoder said. “There’s apparently a mad race taking place to lose what remains of our wetlands and ensure Hoosiers are left completely depleted — literally.

“… Indiana has already permitted nearly all of its wetlands to be developed,” Yoder continued. “When will it be enough? It seems like the supermajority won’t be satisfied until every wetland in the state is eliminated.”

Today is the deadline for Holcomb to sign — or veto — HEA 1383. If he does not sign it, the bill can become law without his signature eight days after it was received, on Feb. 7.

At Indiana Lawyer deadline, it wasn’t clear what his decision would be.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.