Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowThe process of becoming a naturalized United States citizen can be a lengthy one, with applications to submit, interviews to complete, fees to pay and, at the end of the road, the citizenship test.

The test consists of three main parts — written and spoken English, plus civics — that may soon see some changes. Those would be the first changes to the test since 2008, with the exception of a few small updates to some of the questions.

Former President Donald Trump changed the test in 2020, adding more questions and raising the threshold for passing, but many advocates raised concerns that the new version was biased and unnecessarily burdensome.

The Biden administration reverted to the 2008 test in early 2021, with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services releasing a statement saying it had “determined the 2020 civics test development process, content, testing procedures, and implementation schedule may inadvertently create potential barriers to the naturalization process.”

Now, the Biden administration is introducing its own revisions that are also facing some pushback.

“USCIS is developing the trial test for the naturalization test redesign in response to feedback that USCIS received from stakeholders about the standardization and structure of the naturalization test,” a Dec. 15, 2022, notice on the Federal Register said. “USCIS is conducting the trial as part of its effort to redesign the naturalization test to better ensure that the English-speaking part of the English Language requirements is standardized and sufficiently tests the ability to understand words in ordinary usage in the English language.

“Further, during the trial testing USCIS would be assessing the understanding of English through the questions or prompts given with the speaking test instead of using the interview questions and Form N-400,” the notice continued. “However, in the trial testing, USCIS would not assess the understanding of English as part of the reading and writing portions of the naturalization test.”

Proposed changes

The existing exam already includes a speaking portion, during which applicants must be able to say information included on their applications.

Under the proposed changes, applicants would be presented with a photograph and would have to describe, in English, what they see.

Rachel Van Tyle, director of legal services at Exodus Refugee Immigration in Indianapolis, said that would put more pressure on the applicants.

“I speak Spanish pretty well, but there are things in photos I couldn’t describe, right?” Van Tyle said. “Like I wouldn’t be able to find the word ‘sport,’ necessarily, especially if I was in a high stress environment. I don’t think it’s reflective of whether somebody has enough English to make it in this country.”

Van Tyle recalled a woman whom Exodus helped who was around 75. The woman attended thousands of hours of English classes but still couldn’t pass the test.

Other changes include making the civics portion of the test multiple choice, rather than oral short answers.

Under the current test, applicants are asked questions such as, “Who was the first president of the United States?” They then answer verbally.

With the changes, applicants could be presented with a question such as, “Pick an amendment to the United States Constitution that is included in the Bill of Rights.” Rather than remembering one of the first 10 amendments that comprise the Bill of Rights, an applicant would have to know all 27 of the constitutional amendments, as the multiple-choice options could include amendments not in the Bill of Rights.

“In theory it sounds easier, (but) it’s actually going to make it much harder,” Van Tyle opined.

She added that the path to citizenship varies depending on an applicant’s status when they arrive in the U.S.

For example, refugees first have to file a petition for asylum, which can take years to be approved. To apply for citizenship, they must be a lawful permanent resident for at least five years.

After filing the petition for citizenship, refugees must show they are of good moral character. Being behind on child support or having a criminal record can prevent an applicant from applying for citizenship.

Possible hurdles

Van Tyle said Exodus gets around 100 clients annually seeking citizenship, and one of their biggest hurdles is learning English.

Peter Claassen, legal supervisor at the National Immigrant Justice Center, said he understands the desire to make changes to the exam.

But Claassen also said he feels the current test is comprehensive.

“I think the concern from the advocacy side is that anything that makes it more onerous or more difficult is not necessarily a good thing and makes it more difficult for especially the most vulnerable people, refugees, people that maybe have suffered more trauma in the past,” Claassen said.

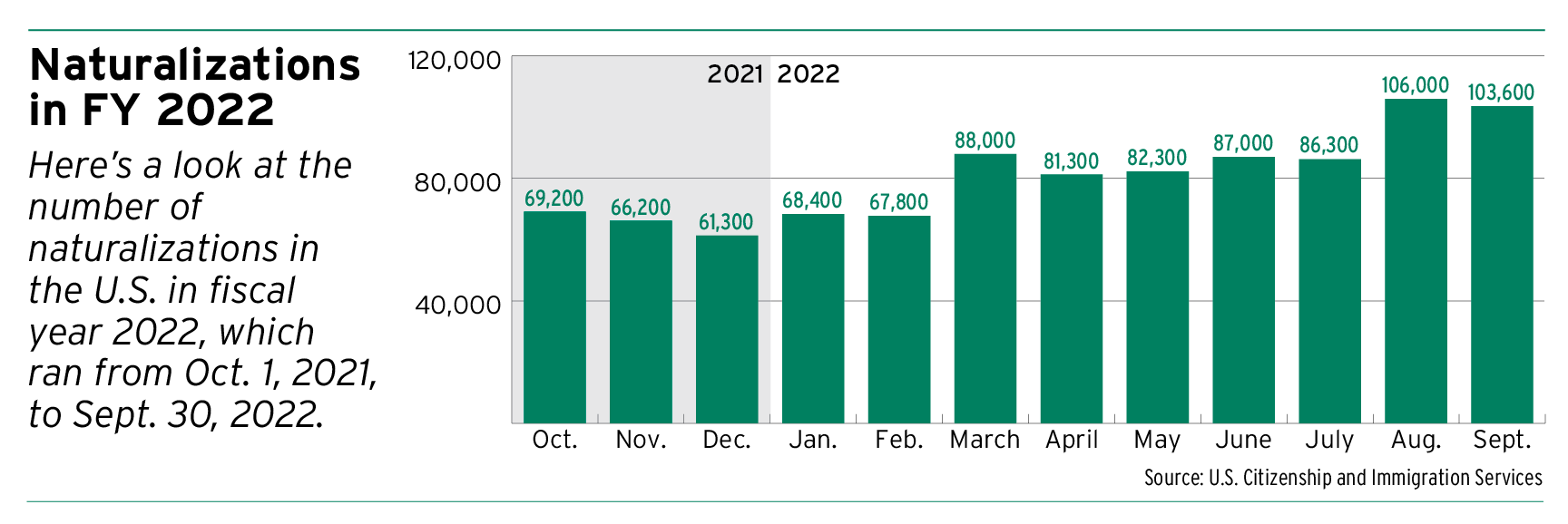

In Fiscal Year 2022, USCIS reported that 967,500 people became new citizens — a 20% increase from FY2021 and the highest number since FY2008.

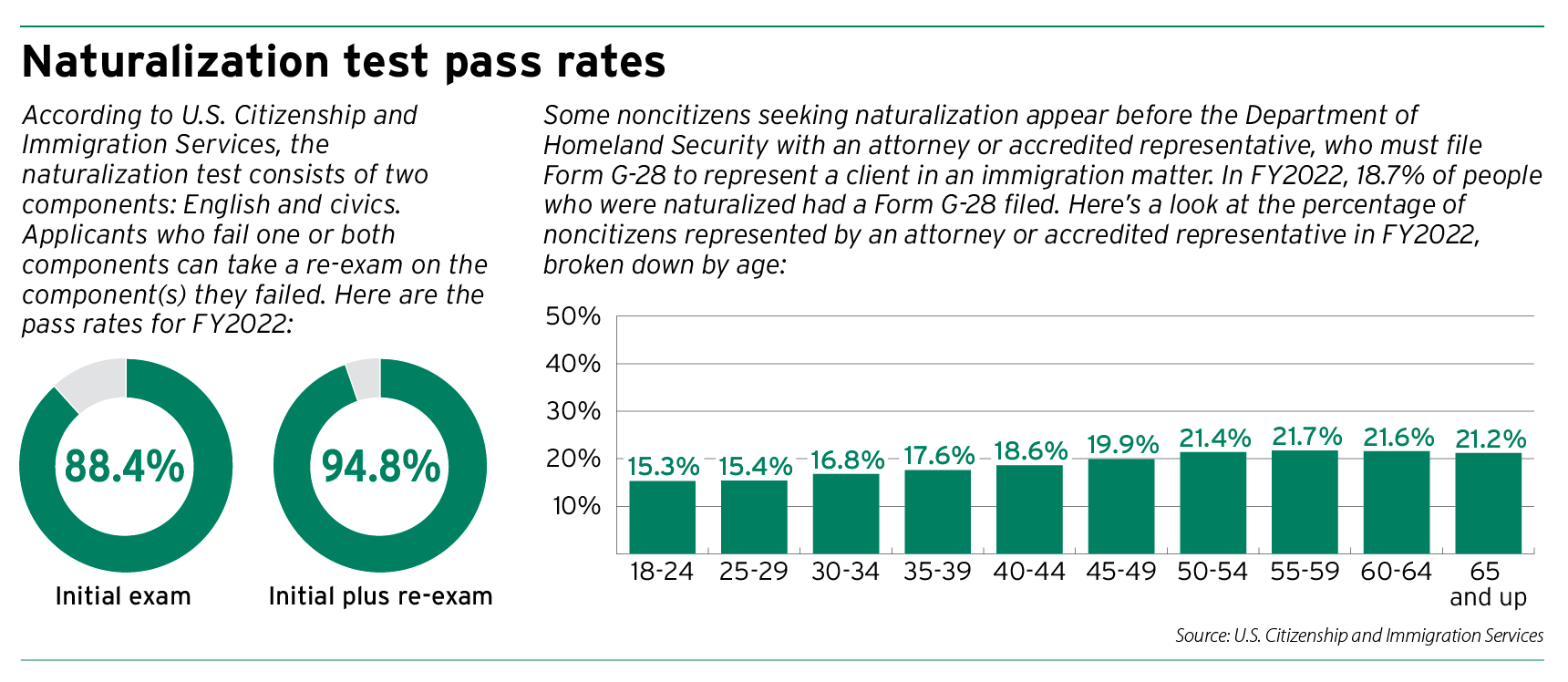

In FY2022, 88.4% of applicants passed the test on their first try while 94.8% passed after taking a re-exam.

If an applicant fails the English or civics portion the first time, they are automatically signed up to take the test the next time it is available without paying.

The test itself costs $725, but with the hiring of immigration attorneys, people can end up paying thousands of dollars to become a citizen.

Once an applicant passes the citizenship test, a naturalization ceremony is held to honor the new citizens, give them their certificates and provide them with resources they need.

In Indiana, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District holds at least two naturalization ceremonies each month, including a ceremony this year held just before the Fourth of July.

Civics education upgrade

One of the common arguments about the citizenship test is whether natural-born U.S. citizens would be able to pass it.

In 2022, Gov. Eric Holcomb signed a law requiring high school students to take the test as part of their civics education. They don’t have to pass the test, but they have to take it to graduate.

Chuck Dunlap, president and CEO of the Indiana Bar Foundation, said the foundation hasn’t yet seen the results from Indiana high schoolers.

The foundation is currently working with sixth-grade teachers on implementing a civics education course that was mandated by the General Assembly and approved by the State Board of Education.

“We’re excited about that and excited about the opportunity to have students start learning more about civics at an earlier age and go into more depth, because they did have some civics before, but it was in the context of a larger social studies course and curriculum,” Dunlap said. “By pulling it out as a separate, standalone, semester course, teachers will be able to go into more depth and more detail and cover more information.”

Dunlap added that Indiana will be one of only seven states to have a full semester of civics in middle school. The course is expected to begin in the spring semester of the upcoming school year.

“We’re excited about the opportunity and look forward to, again, providing the teachers with the resources that they need to hopefully hit the ground running in January,” he said.

What’s next?

According to the Federal Register, USCIS planned to introduce trial testing of the new exam in January, with the trial expected to run for five months.

The full Naturalization Test Redesign Initiative is expected to take approximately two years, with implementation likely coming in late 2024.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.