Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now

Before he started watching virtual hearings, Victor Quintanilla expected to see a lot of litigants who appeared out of sorts on the screen because they did not have the cameras on their phones or computers positioned properly.

Instead, what he actually saw was a lot of black squares. Many of the litigants, especially the self-represented, could not switch on the video, so they were phoning into the proceedings.

The Indiana University Maurer School of Law professor is now leading a study that takes a closer look at how the technology that made virtual hearings possible is helping — and hindering — pro se parties. Focused exclusively on Indiana courts, the research project hypothesizes that the self-represented face additional biases for things like having spotty internet connections or making the call from a noisy place.

Indeed, 18 months into the COVID-19 pandemic that forced the judicial system to quickly transition to remote hearings, many still do not know how these litigants are being impacted.

“We need to learn more about what actually happens here and what can be done to improve these processes,” Quintanilla said. “… We have a lot of anecdotal evidence, people can talk about what they seem to be seeing, but we don’t have carefully designed empirical projects that can actually reveal to the world what’s happening.”

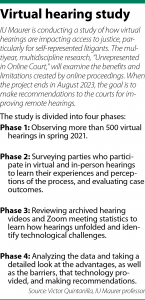

The project, “Unrepresented in Online Court,” started in the spring with IU Maurer and Stanford University law students watching more than 500 livestreamed eviction, debt collection and family law proceedings. As the research continues over the next two years, Quintanilla and his team will be surveying litigants to find out more about their experiences in virtual court. Then they will analyze the responses and again observe the hearings before releasing a final report and recommendations in August 2023.

The project, “Unrepresented in Online Court,” started in the spring with IU Maurer and Stanford University law students watching more than 500 livestreamed eviction, debt collection and family law proceedings. As the research continues over the next two years, Quintanilla and his team will be surveying litigants to find out more about their experiences in virtual court. Then they will analyze the responses and again observe the hearings before releasing a final report and recommendations in August 2023.

“It’s clear that the civil justice system in the future will likely have a component of virtual hearings because of so many of the benefits,” Quintanilla said. “The question, I think, is what can we learn about what happened and what’s happening now, so that we can ensure that this future unfolds in a way that is more fair, more equitable, more effective and efficient?”

Recently, the Pew Charitable Trusts provided financial support and is helping with the research and quality control, according to Erika Rickard, Pew project director for civil legal system modernization. Neither Rickard nor Quintanilla would disclose the amount of funding from Pew.

The IU Maurer project is not alone, as court leaders across the country are taking different approaches to assessing the consequences of remote hearings. Rickard explained the courts are trying to determine which proceedings and processes will revert back to the way things were pre-March 2020 and which innovations and initiatives that have taken place over the course of the pandemic should continue.

As such, the IU Maurer study is the farthest along in terms of connecting with the court system and doing the research on self-represented litigants, Rickard said. The project will be especially helpful to the courts in two key areas.

First, she said, it will offer the voices and perspectives of those litigants as they navigate the judicial process. And second, the data will help the courts be more precise about where an intervention program is needed to aid the pro se parties.

“Courts have been more willing to change and more willing to be responsive to the needs of today’s court users than ever before,” Rickard said. “And what we want to do is to be able to provide some empirical grounding for how they can … make sure that today’s court meets the needs of today’s user.”

Bright spots and hot spots

The IU Maurer project is drawing on experts from disciplines outside of the legal profession. Key partners in the study are Kurt Hugenberg, IU professor of psychological and brain sciences; Margaret Hagan, director of the Stanford Legal Design Lab; and Amy Gonzales, University of California Santa Barbara associate professor of communication and information technologies.

Quintanilla said the nonlegal experts will foster a deeper understanding of the data. Hugenberg, for example, has studied the snap judgments and decisions about credibility that people make based just on seeing another individual. That “person perception” knowledge will provide additional insight into what is happening in the virtual hearings.

“One of the things that we’re going to be able to do coming out of this, I think, is this realization that some of the most difficult access to justice problems that we’re dealing with, we can’t solve only by drawing on one approach,” Quintanilla said. “It’s going to require multidisciplinary approaches.”

Also helping with the project is the Indiana Coalition for Court Access and the Indiana Supreme Court.

Already, the coalition, which is overseen by the Indiana Bar Foundation, has been focused on how the legal needs of the indigent can be best served and, prior to the pandemic, was starting to examine the use of technology in the courts. Through its work, the coalition has become familiar with what Quintanilla called the bright spots and hot spots of virtual hearings.

Charles Dunlap, president and CEO of the foundation and member of the coalition, and Marilyn Smith, vice president and director of civil justice programs at the foundation, explained that one bright spot is the convenience of being able to appear at an online proceeding from just about anywhere. But there are multiple hot spots regarding due process rights, the ability to deliver evidence and ensuring equity for litigants who do not appear on a judge’s computer screen because they dialed in.

Dunlap and Smith said they see a willingness in the judiciary and the practicing bar to develop any interventions that the IU Maurer project recommends to help pro se litigants. That may include creating spaces in public libraries or social service agencies where litigants can tap into reliable internet and attend a hearing, or enlisting navigators to assist litigants as they work through the court process.

“Everybody sort of feels like they’re on the same plane and the turbulence is strong,” Smith said. “There’s a commonality that allows people, perhaps, to be a little more open right now.”

At the Indiana Office of Judicial Administration, Bob Rath, chief innovation officer, and Kendra Key, staff attorney with the court’s Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, likewise said they see the potential for the IU Maurer project to help the courts with “continuous improvement.”

They echoed many in saying virtual hearings will likely remain in some fashion, so the research is needed to help answer the questions that have come with the shift to online. The IU Maurer study could highlight not just the limitations but also the advantages of online hearings and perhaps shed light on how to improve court access even after the pandemic ends.

“If we learn something that’s really deep and meaningful about how we interact with the courts, and we can continue to benefit not just as a court but … court users in general from this research that we’re doing right now, I think that would be that would be wonderful,” Key said. “That would be a great outcome of just this one research project and break open even more for us to look at and improve upon.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.