Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowPublic confidence has declined as safety and effectiveness are questioned

One consistent message throughout the COVID-19 crisis has been that life will start returning to normal once a vaccine arrives.

Yet even while the virus continues to rage around the world and pharmaceutical makers get closer to developing an effective vaccine, Americans’ willingness to get inoculated has slipped. Surveys show a marked drop in the number of individuals who say they would get a COVID-19 vaccine if one were available. The primary concern is the medication has been developed too quickly and it will be approved before its safety and effectiveness are fully understood.

Any battle over the vaccination will probably spill into the workplace. Employers are already starting to consider policies and plans for ensuring their workers’ health along with making possible accommodations to those who object to getting the shots.

Jimmy Robinson Jr., office managing shareholder for Ogletree Deakins Nash Smoak & Stewart in Richmond, Virginia, said employers are regularly contacting him with questions about the coronavirus vaccine. They are concerned about keeping their offices and facilities safe so their employees are not exposed on the job.

Robinson’s advice to clients is simple. “Prepare, prepare, prepare, prepare,” he said. “Employers have to be prepared.”

Among the things companies have to analyze is whether to issue a mandate. They will have to make decisions about not just how to implement such a directive but also what to do if employees refuse to get the COVID-19 vaccine.

“Employers have to be prepared for public distrust of the vaccine,” Robinson said.

Direct threat

That distrust has been growing. Surveys by Pew Research Center showed the percentage of individuals who said they would get a COVID-19 vaccine if one were available had dropped from 72% in May to 51% in September. A Gallup Panel survey conducted from Oct. 19 to Nov. 1 recorded a rebound in the share of Americans willing to be vaccinated, with 58% saying they would get inoculated compared to 50% in September.

Concerns about misinformation surrounding the COVID-19 vaccine prompted the American Medical Association House of Delegates to adopt a new policy during a special meeting Nov. 17. The goal is to educate physicians on how to address patient apprehension, dispel misinformation and build confidence in the vaccination. In particular, the AMA is being especially attentive in its outreach of communities of color given the history of experimentation with vaccines on minorities.

Ross Silverman, a professor who teaches at both the Indiana University Richard M. Fairbanks School of Public Health at IUPUI and the Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law, said the mixed messages about the vaccine has fed some of the inaccurate information floating around. But the public health community, regulators and the pharmaceutical companies are being as transparent and providing as much information to the public as they can.

“There has probably never been a more anticipated medical discovery than a COVID-19 vaccine,” Silverman said. “There are more eyes watching this process than almost anything that I’ve seen as far as sort of development of new interventions.”

“There has probably never been a more anticipated medical discovery than a COVID-19 vaccine,” Silverman said. “There are more eyes watching this process than almost anything that I’ve seen as far as sort of development of new interventions.”

The direct threat posed by COVID-19 might push the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission as well as the courts to give employers a little more leeway.

Barry Hartstein, chair of the equal employment opportunity and diversity practice group at Littler Mendelson P.C. in Chicago, pointed to the H1N1 outbreak in 2009 when many health care workers were required to get a flu vaccine.

Similarly, businesses can mandate their employees get inoculated for COVID-19, but they may have to accommodate those employees who refuse.

Workers could seek an exemption under federal law from any vaccine mandate. Title VII will allow them to refuse on the basis of their sincerely held religious beliefs and the Americans with Disabilities Act will provide for objections because of disability or medical condition.

Employers could counter by citing the undue hardship standard. Businesses may claim that having a worker who is not vaccinated or the requirements for accommodating the unvaccinated worker places an undue burden on their operation because it puts others at risk of COVID-19.

Still, in a report written by Hartstein and other Littler attorneys, the law firm advised employers to consider initially encouraging vaccinations rather then setting a requirement. A mandate could get individual employees seeking accommodation as well as groups of employees challenging the mandate on political grounds. Additionally, a company could face workers’ compensation claims if the vaccine causes any adverse effects.

Indiana RFRA

State and federal courts might begin seeing cases involving COVID-19 mandates as employers and employees work through some of the issues.

State and federal courts might begin seeing cases involving COVID-19 mandates as employers and employees work through some of the issues.

Workers trying to shield themselves with Indiana’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act could be presenting the courts with a case of first impression. Silverman noted some churches have invoked RFRA to push back against state-imposed limits on the number of people allowed to attend an indoor worship service. But, he said, using RFRA to get an exemption to a vaccine mandate has yet to be tried.

If RFRA is cited in a legal proceeding over a vaccine requirement, the workers might have to provide some proof of their religious beliefs. Robinson pointed out that claiming a religious objection under Title VII puts a burden on the individual to prove the beliefs are “sincerely held,” but Indiana did not include such an inquiry in RFRA. In court, that could change with workers being pressed to offer some evidence how their religion and practices prohibit vaccinations.

The EEOC has not issued any guidance to date on COVID-19 vaccines, preferring to wait until the medication is available before offering advice. Silverman is expecting the EEOC will shy away from mandates and recommend that employers “strongly encourage” their employees to be vaccinated.

Still, both Hartstein and Robinson pointed out that already employers are being permitted to take a few more liberties in dealing with COVID-19. They are able to ask questions about whether employees have been exposed to the virus and if they are experiencing symptoms. Also, they can take the workers’ temperatures, which actually constitutes a medical exam — something they previously had not been permitted to do.

Adding another twist to the desire to return to normal is the limited quantity of vaccines that will initially be available. Manufacturers will have to scale up production and meet demand around the world.

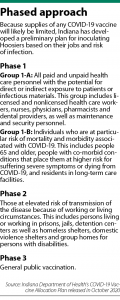

In anticipation, the Indiana Department of Health has drafted a plan identifying the groups who would be inoculated first whenever the first batch of the vaccine arrives. The committees looking at allocation plans and ethical considerations included representatives from IU McKinney.

Silverman, who also help developed the health department’s plan, said the legal professionals assisted in crafting the distribution process. Consideration has to be given to who would be receiving the first doses and ensuring the rollout procedure is practical to implement.

“Lawyers are contributing in making sure that we’re lining up the science with issues of justice and equity while also trying to keep the process grounded in the reality of the logistics and what we understand about how the vaccine is going to be distributed, where’s it’s going to be distributed, etc.,” Silverman said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.