Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowThe pictures of sun-drenched homes and neatly trimmed lawns in East Chicago showcase what is perhaps the best outcome.

However, the images belie the nightmare many residents are still living. The homes along with the neighboring West Calumet Housing Project and Carrie Gosch Elementary School were all built on the USS Lead Superfund site.

For decades, lead refineries, a lead smelting plant and a manufacturer of white lead operated on the property. When the companies shuttered the facilities, the lead remained in the soil.

In 2009, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency listed the USS Lead site on the National Priorities List for contamination cleanup. The high levels of lead were discovered at least as early as 1985, but officials did not take action until 2016, when the nearly 1,100 residents of West Calumet, about 680 of whom were children, were ordered to relocate.

Remediation of the property has entailed scooping out the top layer of dirt and replacing it with clean fill and topsoil, according to reports by the EPA.

Cleaning a contaminated site can take years, said Allison Wells Gritton, partner of counsel in the Indianapolis office of Dinsmore & Shohl. She focuses her practice on the remediation of toxic properties, but she is not doing any work related to the USS Lead Superfund.

The work to restore the land or groundwater at a distressed site begins with extensive testing in various seasons to determine the extent of the contamination. Next comes a proposed plan and an approval process, then the cleanup follows. Afterward come several months of testing, a review of the results and, if needed, another round of remediation.

During the entire process, Gritton said, the residents in the community should be kept informed as to what is happening.

“It is just kind of a very foreign area for most people and highly technical,” she said. “This can be daunting and scary.”

Many residents in East Chicago say they were not alerted to the contamination and, in fact, some allege the level of pollution was intentionally concealed from them.

Lawsuits have been filed in state and federal courts as individuals and families seek restitution for their injuries. Indianapolis attorney Eric Pavlack of Pavlack Law is part of a legal team that is representing what he called the largest collections of plaintiffs who are seeking damages for physical and neurological injuries.

“It shocks me not just as a lawyer but as a parent and member of society that so many people, so many entities, private and public, would allow this to go on,” Pavlack said of the contamination. “I think it’s almost indisputable that the reason this was allowed to happen is because this is (an) … underserved and poor population that doesn’t get the same care that others do. Frankly, it’s disgusting and it’s just heartbreaking.”

‘Missed opportunities’

The plaintiffs in Pavlack’s cases allege public and private officials knew about the toxic mess for years before telling the public.

The plaintiffs in Pavlack’s cases allege public and private officials knew about the toxic mess for years before telling the public.

West Calumet Housing Complex was completed in 1972 and plaintiffs allege the state knew the land was contaminated before construction began, according to Pavlack. The state had a “great deal of knowledge about the pollution,” he said, but “despite repeated red flags, officials didn’t tell people that their kids were playing on ground that would expose them to lead” and cause myriad disorders and health problems.

Similarly, the plaintiffs claim the manufacturing defendants failed to reveal the full extent of the contamination. Pavlack said the companies that operated on the site “polluted the land with what is just an extraordinary and unimaginable amount of lead and arsenic.”

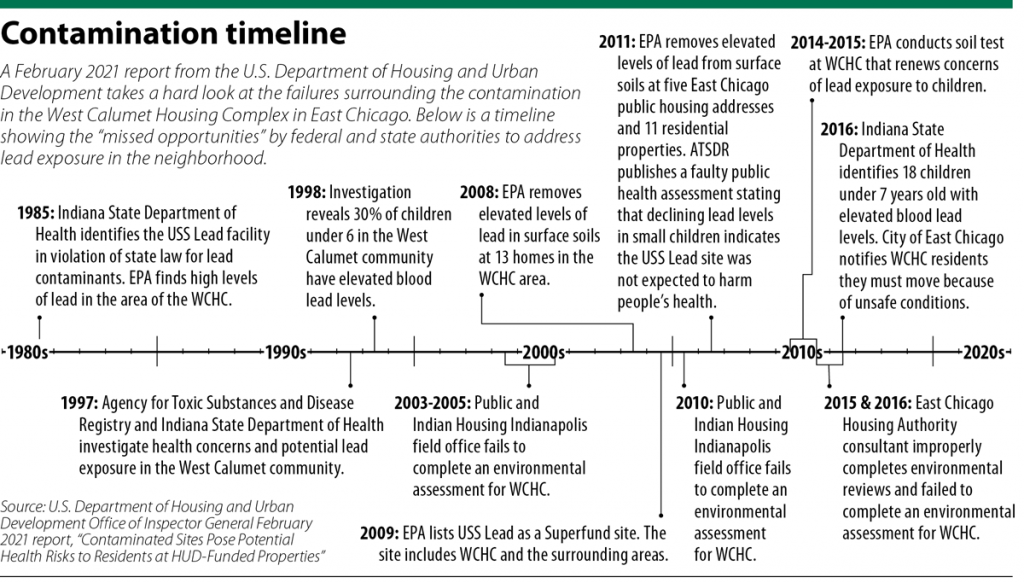

A February 2021 report from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development seems to echo some of the plaintiffs’ allegations. The study, “Contaminated Sites Pose Potential Health Risks to Residents at HUD-Funded Properties,” takes a hard look at West Calumet and concludes federal, state and local authorities “missed opportunities” to identify site contamination and notify the residents of the dangers.

The Indiana State Department of Health and the EPA found problems with lead on the West Calumet property in 1985. Thirteen years later, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry recommended lead contamination remediation, and in 2009 the EPA added the USS Lead Site, upon which West Calumet was built, to the Superfund National Priorities List.

However, according to the report, officials did not take action. East Chicago Housing Authority members attended EPA meetings in 2009 and 2011 about the testing for lead in the homes and the need to remove soil with elevated levels of lead, but the authority’s executive director said she was not aware of the contamination at West Calumet until 2016.

Also, the report found that the Public and Indian Housing’s Indianapolis field office did not adequately conduct or oversee environmental reviews going as far back as 2003.

As a result of “multiple missed opportunities,” the residents in the housing complex “continued living in unsafe conditions for decades, and inadequate oversight led to the lead poisoning of children… ,” the report stated. “Between 2005 and 2015, a child living in (West Calumet) had nearly a three times greater chance of having elevated blood lead levels than children living in other areas of East Chicago.”

Litigation

Of the cases Pavlack is helping to litigate, two notched key court decisions in 2020.

The Indiana Court of Appeals kept alive the plaintiffs’ lawsuit against governmental entities in State of Indiana, Indiana Department of Environmental Management, Indiana State Department of Health, et al. v. Cristobal Alvarez, C.A., by next friend Cristobal Alvarez, et al., 19A-CT-587.

Also, the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals overturned an attempt by the plaintiffs to get their complaint against several manufacturers remanded to state court in Sherrie Baker, et al. v. Atlantic Richfield Company, E.I. du Pont De Nemours and Company, et al., 19-3159 and 19-3160.

Before the Court of Appeals, the state argued, in part, that it was entitled to immunity under the Indiana Tort Claims Act. The defendants asserted their alleged failure to warn the plaintiffs about the elevated levels of lead and other toxins involved “making a political, social and economic judgment,” which are planning functions that are discretionary and subject to immunity.

A unanimous appellate panel was not convinced. The judges held that based on the pleadings, they could not say as a matter of law that warning citizens of possible lead exposure

is a planning function.

According to Pavlack, the case is back in Lake Superior Court, where the judge has entered a case management plan that includes a schedule for discovery. The defendants have filed motions to dismiss.

Likewise, the manufacturer defendants in Baker have filed their motions to dismiss with the Northern Indiana District Court.

The plaintiffs allege the defendants “actively concealed” the extent of the contamination so that families and children lived on a “toxic waste dump” with no knowledge of the dangers to which they were continually exposed. They state a handful of claims against the manufacturers including strict liability, negligence and intentional infliction of emotional distress, and ask for punitive damages in the amount of $100 million.

Defendant Atlantic Richfield pointed to one other lawsuit brought by former West Calumet residents, Rolan v. Atl. Richfield Co., 1:16-cv-357. There, the Northern Indiana District Court had dismissed the negligence claim, finding Atlantic Richfield owed no duty to those who occupied the land that the manufacturer’s alleged predecessors once owned.

In its motion to dismiss, DuPont asserted it did not owe plaintiffs a duty needed to support the negligence claim. The company stopped manufacturing lead arsenate products in 1949, and at the time it was operating, it was “not reasonably foreseeable” that the site would later be converted into a residential housing complex.

West Calumet no longer exists. The 346-unit housing project has been demolished and the residents, according to Pavlack, have resettled, some in East Chicago and some out of state.

“Many of the plaintiffs are people who lived pretty difficult existences before this came to light,” he said, “so not surprisingly, to suddenly be told that you have to suddenly move out of the place … wasn’t easy.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.