Subscriber Benefit

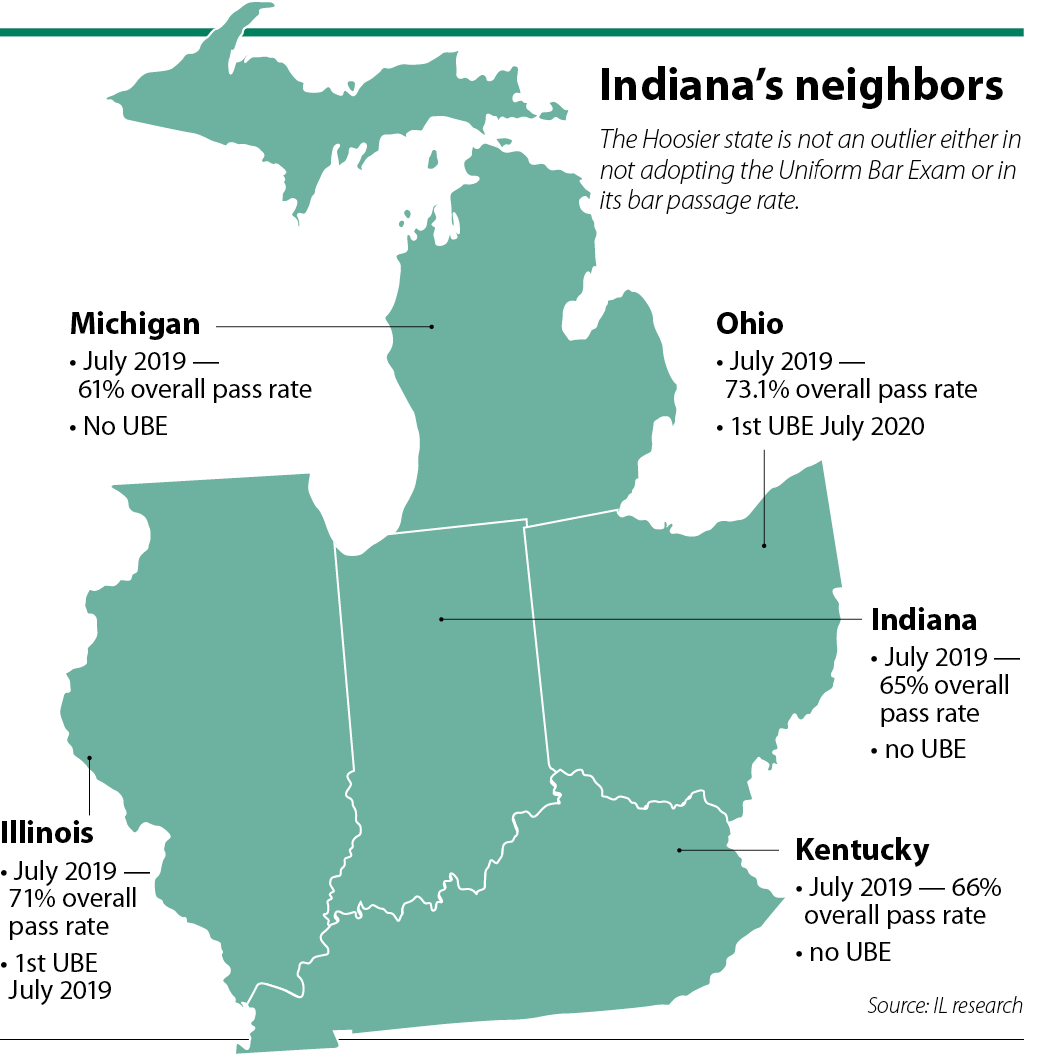

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now Of Indiana’s four neighboring states, one has adopted the Uniform Bar Exam, one is preparing to adopt, one is expected to adopt and one is not even considering adoption.

Of Indiana’s four neighboring states, one has adopted the Uniform Bar Exam, one is preparing to adopt, one is expected to adopt and one is not even considering adoption.

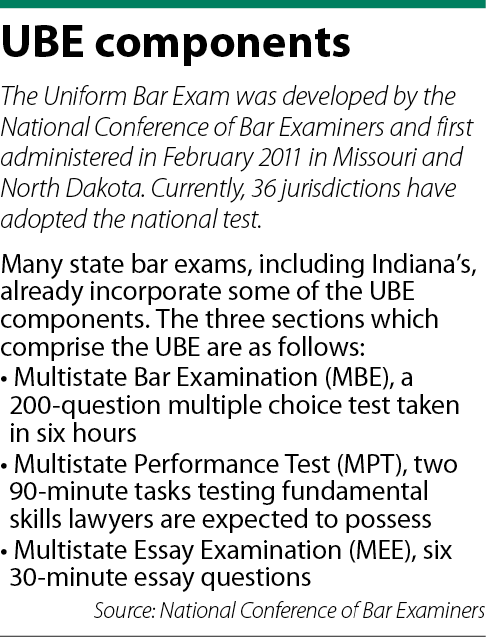

The Study Commission on the Future of the Indiana Bar Exam has completed its review of the state’s bar exam and is now recommending the Hoosier state join the UBE movement. Since Indiana already uses the Multistate Bar Exam and the Multistate Performance Test components of the UBE, completely transitioning would require the Indiana essay portion to be replaced with the Multistate Essay Exam.

However, the UBE recommendation was not unanimous. Three members of the commission opposed the switch, asserting Indiana would lose control over its own bar exam and the examinees would not learn substantial Indiana law prior to admission.

The arguments for and against UBE adoption have been the same in each jurisdiction that has considered the uniform test. Proponents cite the exam’s well-crafted questions and the ability of the examinees to take one bar but potentially be licensed to practice in multiple states, while opponents raise concerns about new lawyers being admitted without knowing the unique laws and nuances of practicing in a particular jurisdiction.

Currently, 36 states use the UBE. Below is an overview of what Indiana’s neighbors are doing.

Illinois

The Land of Lincoln switched to the UBE in July 2019, about three years after the Illinois State Bar Association endorsed a recommendation that the state adopt the national test. To make the transition, the state dropped the three Illinois-specific essay questions and picked up the second MPT question. The state had been incorporating in its exam one MPT query along with six MEE questions and the multiple-choice MBE.

Like Indiana, some in Illinois expressed reservations about eliminating the Illinois-distinctive section of the bar exam, according Daniel Thies, an attorney with Webber & Thies in Urbana, Illinois, who led the Illinois State Bar’s Standing Committee on Legal Education, Admission and Competence in its evaluation of the UBE. Yet after discussion and review, the opposition dissipated, and when the UBE was implemented, few seemed to notice.

“From my perspective, it was a non-event,” Thies said of the Illinois’ first UBE. “Practicing lawyers didn’t pay much attention to it.”

The concern about losing the Illinois section of the exam was mitigated somewhat by the realization that the method of scoring meant an examinee could, in fact, fail all the state-law questions but still pass the bar. Also, Thies said, skeptics were won over by the argument that adopting the UBE would give the state more flexibility to implement a rigorous program to ensure new lawyers know Illinois law.

Currently, the state requires all new admittees to complete a 15-hour continuing legal education course on basic skills. In its report, the state bar committee suggested the state adopt additional licensing obligations to bolster familiarity with Illinois law.

Thies advocated that attorneys be required to pass a multiple-choice test focused solely on the state’s laws before being admitted, much like New York mandates. But the Illinois Supreme Court, in its order adopting the UBE, did not implement an additional requirement.

“If I were king of Illinois, I would probably put in something like New York’s multiple choice test,” Thies said. “The basic skills course does something, but I think we could do a little better.”

Ohio

Indiana’s eastern neighbor plans to implement the UBE in July 2020. Like the Hoosier state, Ohio will only have to swap its 12 essay questions for the MEE in order to switch to the national exam since it is presently using the MBE and MPT.

The Task Force on the Ohio Bar Examination, which recommended the adoption of the UBE, also looked at the potential that women applicants could be disadvantaged by the change in scoring that will accompany the UBE.

Essays on the current Ohio exam count for a little more than 53% of the total score. However, the UBE would shift the weight so the MBE’s 200 multiple choice questions would comprise 50% of the score while the multistate essay exam would make up 30%.

Noting other studies have found women don’t perform as well as men on multiple choice exams, in general, the task force worked with Research Solutions Group to review available data and forecast how the outcomes could change for the different genders under the UBE. The task force found the UBE would potentially bring a net change of raising the passage rate for men from 71% to 74% but lowering the passage rate for women from 68% to 66%.

Task force chair Benjamin Barros, dean of the University of Toledo College of Law, said the concern about the gender impact arose from the reweighting. However, Barros noted most states would not need to share that concern because they already use the UBE weighting.

Kentucky

After a multiyear comprehensive review of its bar exam, the Kentucky Supreme Court followed the advice of the Kentucky Bar Admission Review Commission and rejected the adoption of the UBE in December 2016. But retired Kentucky Justice Bill Cunningham, who co-led the commission, expects the Bluegrass State will reverse course since the UBE failed by only one vote back then, and the composition of the state’s supreme court today seems to be more favorable toward the national test.

“I think Kentucky is going to adopt the UBE, it’s just a matter of time,” Cunningham said. “We tend to be followers.”

The Supreme Court did follow the commission’s recommendations in eliminating four subjects from the Kentucky essay portion and adding the MPT. Cunningham and his co-chair, retired Justice Daniel Venters, pushed for law students to be allowed to take the bar exam during the last semester of their studies, but the Supreme Court retained the requirement that applicants must complete their J.D. degree before taking the exam.

By permitting students to take the February bar, Cunningham said he and Venters hoped the third-year curriculum would be revamped in response.

The justices wanted the three Kentucky law schools to include bar preparation in their curriculum so the applicants for admission would not have to pay the $3,000 or more they are shelling out for prep courses now on top of their tuition. Also, the justices envisioned the educational institutions would be motivated to enhance their practical skills training by offering students more hands-on opportunities in their final semester so the graduates would be practice-ready.

Helping lead the review of the bar exam solidified Cunningham’s support for requiring all lawyers to pass a test before being admitted. “I think we need it,” he said, noting the practice of law is like taking a bar exam every day. “I think we have to have it. It adds a distinction to the profession.”

Michigan

Much to the frustration of Otto Stockmeyer, professor emeritus at Western Michigan University Cooley Law School, the Wolverine State appears to have no plans to even consider adopting the UBE. Currently the state’s bar exam consists of 15 Michigan-specific essay questions and the MBE, but the law professor believes the UBE would be an improvement.

“The UBE may not be the be-all-and-end-all, but it is today’s gold standard,” Stockmeyer said. “If (the other states that have adopted the UBE) all feel this is the best way to measure minimum legal competency, why aren’t we looking at it?”

Implementing the UBE would bring the immediate benefit of the MPT, which measures practical skills, Stockmeyer said. Law schools would then have an incentive to provide more hands-on training so the students could learn tasks they will likely do as new lawyers, such as drafting a legal memo or contract.

In addition, replacing the homegrown Michigan essay questions with the MEE would not only greatly reduce the 26 separate subjects bar applicants currently have to prepare for, but would also improve the quality, he said.

The Michigan Board of Law Examiners distributes the essay questions and model answers to law professors for comment after the exam is given. Stockmeyer said in the 35 years he has been reviewing and responding to the questions, he has found some questions test on very obscure parts of the law that most lawyers will never encounter, while others cover the same topics year after year, so examinees know in advance exactly what they will be asked.

“My goal is modest,” Stockmeyer said. “I just want the Michigan Supreme Court to appoint a study commission like Indiana has done.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.