Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowThe town of Kingsford Heights in northwest Indiana looks like a lot of other small towns across the Midwest, with its volunteer fire department, community center and an elementary school that recently celebrated its students making the front page of the local newspaper.

Now, Kingsford Heights, a town of about 1,300 people that’s sometimes called “Victory City,” has something else in common with a growing number of smaller communities: Its town council is facing a lawsuit for allegedly violating the First Amendment rights of its residents — not at the ballot box or in a church, but on Facebook.

A federal lawsuit filed in June by the American Civil Liberties Union of Indiana alleges the town council, through its private Facebook page, has kept residents from receiving information by denying them access to the page, violating their First Amendment right to engage in speech.

The case — Michael Easley, and Emily Galloway v. Town of Kingsford Heights, Indiana, and the Town Council of Kingsford Heights, Indiana, 3:23-cv-0056 — was filed in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Indiana, South Bend Division.

In one example cited in the lawsuit, a man was removed from the page after he posted a comment in another forum that was critical of the town council’s leadership.

Operating a private Facebook page is a First Amendment violation on its own, according to the lawsuit.

The lawsuit provides a link to the town council Facebook page, but the link leads to a page that says the content isn’t available.

“When this happens, it’s usually because the owner only shared it with a small group of people, changed who can see it or it’s been deleted,” a message from Facebook says.

In addition to denying access to some people, the lawsuit says the town council routinely deletes members’ comments.

The ACLU is asking the court to issue a preliminary injunction enjoining the town and town council from maintaining a private Facebook page or, alternatively, enjoining them from refusing access to the page. The ACLU is also asking the court to enjoin the town and town council from deleting comments on the basis of content or viewpoint.

Town Council President Dennis Francis did not respond to a request for comment by Indiana Lawyer deadline. Online court records do not yet list counsel for the town.

Social media becoming ‘bigger tool’ for government

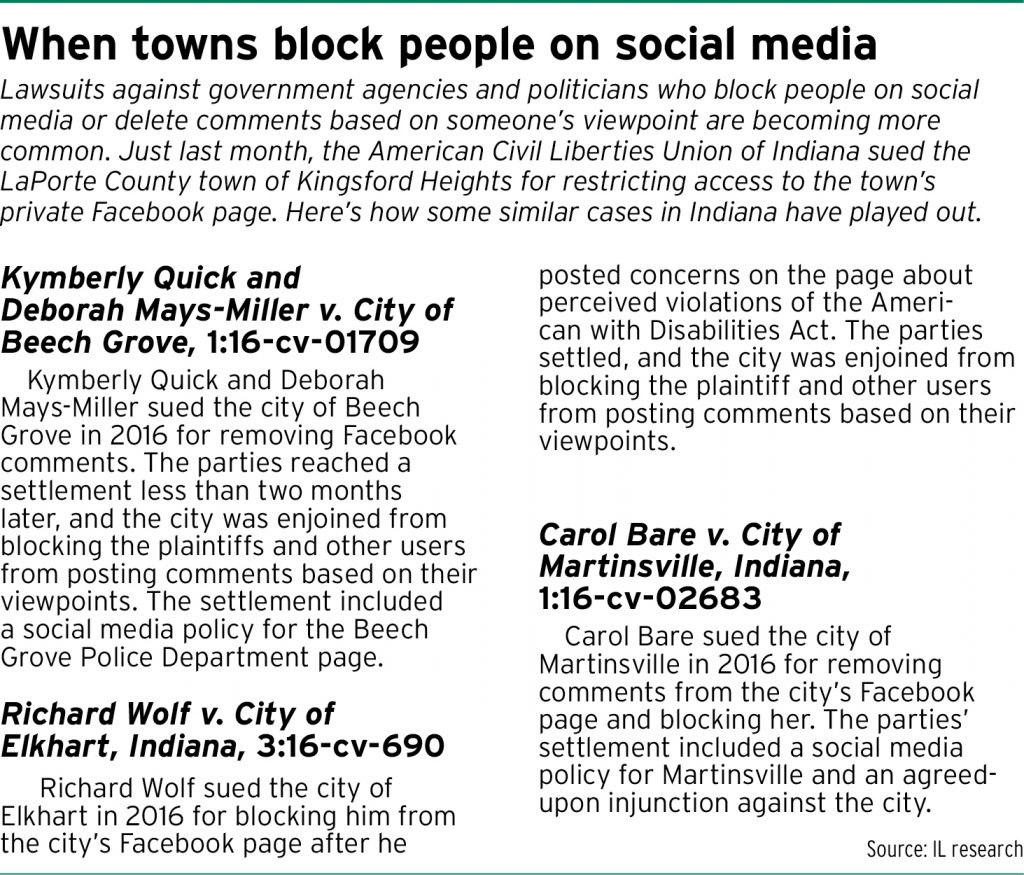

The lawsuit against Kingsford Heights is similar to others that have been filed against towns and individual politicians related to social media.

“I do think social media has become a bigger tool for government to use to communicate with persons, even more recently than 10 years ago,” Gavin Rose, the lead attorney for the ACLU on the case, said.

Rose said his office has filed these types of cases with regular frequency over the last three or four years, and while the vast majority of cases are different in one way or another, the common thread is some form of alleged government censorship.

Hopefully, Rose said, people are taking notice of the lawsuits and adjusting.

“We have no interest in spending our time and resources in litigating case after case after case concerning the same issue,” he said.

Outside of Indiana, Alexia Ramirez, a legal fellow at the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, said such cases are happening “all over the country.” That’s because even though social media isn’t exactly new, government agencies and politicians conducting official business through social media is a more recent development.

Having access to government pages on social media is “critical to modern civic engagement,” Ramirez said.

The Knight First Amendment Institute published a guide in 2020 called “Social Media for Public Officials 101.”

One piece of advice says politicians, if they want to continue blocking people, can keep their accounts personal and not use them for official purposes.

Another piece of advice: “Don’t block users or delete comments just because they criticize you.”

How one lawsuit played out

How one lawsuit played out

A case from 2016 — Carol Bare v. City of Martinsville, Indiana, 1:16-cv-02683 — demonstrates a common progression for these types of lawsuits.

Carol Bare, represented by the ACLU of Indiana, accused the Martinsville Police Department of deleting critical comments she’d posted on the department’s Facebook page after “a series of negative interactions” with Martinsville PD. Bare was also blocked from posting comments.

The censorship, the lawsuit alleged, was based on her expressed viewpoint and therefore was a violation of the First Amendment.

The lawsuit was filed Oct. 7, 2016.

By Dec. 13, the parties had reached an agreement in which the city denied the allegations but agreed to an injunction enjoining it from blocking Bare from posting comments on the police department’s Facebook page and other social media pages maintained by the city based on her expressed viewpoint. The agreement applied to “future users,” too.

Martinsville also agreed to pay $2,517 in costs and attorney fees and to implement a social media policy. The policy said comments would be monitored and “not be removed based on their opinion or viewpoint.”

However, there was still room to remove comments that included true threats, obscenities, defamation and other things.

If a comment was to be removed, the agreement said the moderator would notify the user and explain the removal.

Why smaller communities?

When lawsuits name a city or agency as the defendant, there’s an apparent theme that it’s usually a smaller town.

Rose, the ACLU attorney, said a “fair share” of cases are against smaller towns, guessing it could be partly because government officials in tight-knit communities are more likely to take criticism personally.

Plus, he said a small town probably isn’t as likely as a larger city to have a social media policy that’s vetted by a city attorney.

As a proxy for what larger cities might have in place, Indiana Lawyer asked Sara Hindi, a spokesperson for the Indianapolis City-County Council, how the local council handles social media.

Hindi said while the council doesn’t have an “official” social media policy, councilors and staff are told government accounts are subject to First Amendment scrutiny and public records laws.

David Greene, civil liberties director and senior staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said he’s been doing free speech work for about 26 years. Cases like the one against Kingsford Heights started “bubbling up” around 2016 or 2017, he said.

Greene also guessed cases tend to skew toward smaller towns because larger cities probably have a legal staff to give advice and avoid litigation even if issues do pop up.

Small towns and their local officials just don’t get that luxury, he said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.