Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIn the estate planning world, preparing for an individual’s future and a business’s future can be two separate tasks. An individual might have clearly designated heirs, but a business owner’s successor might not be obvious.

But the two aren’t completely separate. A business succession plan can have a direct impact on how a business owner divides his estate among his children, and vice versa.

Given this complicated reality, Indiana estate planning and business succession attorneys say often, business owners don’t like to think about what might happen to their company if they were no longer able to run it. This is also true nationwide, with Forbes reporting that 30% of businesses don’t have a formal estate plan in place.

That proves to be a complication if an owner unexpectedly dies or can’t run their business for another reason. Then, it’s left to attorneys, financial advisers and family members to sort through the details and keep the company running.

Regardless of what form it takes, estate planning and succession attorneys all implore their clients in the same way: put a plan in place. Business owners generally are in the best position to plan for the future of their company, attorneys say, so leaving succession planning to the heirs can do more harm than good.

“It’s just a different animal,” said Rodney Retzner, an estate planning and business succession attorney with Kreig DeVault in Indianapolis. “It’s not like mom and dad have $10 million in stock, which passes on in equal shares. If the $10 million is a family-owned business, the planning is drastically different.”

Pushing past procrastination

There are different reasons why an entrepreneur might procrastinate on creating a succession plan, attorneys say.

Mark Pfeiffer, an estate planning attorney with Harrison & Moberly, said owners often are caught up in their work and don’t want to think about the future. Retzner agreed, adding that if a business owner is prompted to proactively create a succession plan, the plan must be produced quickly before the owner’s attention returns solely to their day-to-day work.

Matt Folz, a Peru lawyer who works mostly in the agricultural industry, said personalities can also affect a person’s decision to create a business plan. Farmers, for example, tend to be very private and very invested in their land, Folz said, so they may wait until as late as their 80s before planning for the future.

In Pfeiffer’s experience, business owners will begin thinking about creating a succession plan while they are drafting their personal estate plans. Retzner said clients will often want to draft a plan when they’ve had a death in the family, when a parent wants to retire, or when a lender asks them to provide a succession plan.

Retzner, who also teaches an estate planning and business succession class at Indiana University Maurer School of Law, said he gives his clients and students the same advice: when starting the process, always begin with the core documents.

“If you were to die today, where would things go, who’s in charge, how does that flow?” Retzner explained. “You need that core estate planning.”

Fairness vs. equality

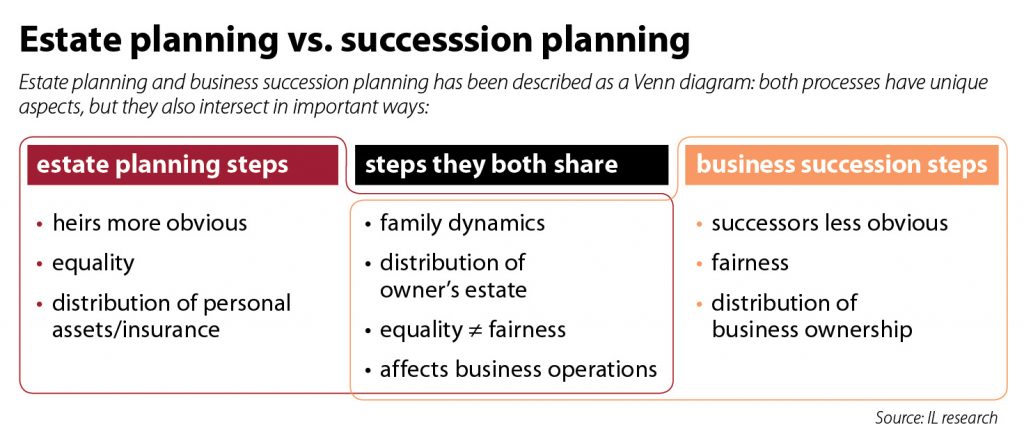

Pfeiffer describes the business succession planning process as a Venn diagram: individual estate planning and business succession planning are two separate processes, but there’s necessary overlap.

From a purely business perspective, an owner needs a “contingency plan,” Pfeiffer said: what would happen to the business if the owner were hit by a bus? But that owner also needs to answer the same question regarding his personal assets, which is where the two concepts intersect.

Ryan Leitch, who practices at Riley Bennett Egloff, said an owner may not want their ownership to pass to the person’s heirs in the same way their individual assets would. There may be a colleague better suited to take over operations, he said, or one of the owner’s children who works at the business may have been groomed to take the helm.

But what if the owner has other children who aren’t involved in the business? That situation, Leitch said, may raise discussions about the difference between fairness and equality.

Often, parents who own a business operate with the assumption that their estate, including the company, will be divided equally among all children. But that’s not always practical, nor is it always the best plan for the company.

“Something that comes into play in succession planning is the concept of fairness and equality,” Leitch said. “They’re not always the same thing in succession planning for business.”

Leitch gave the example of a business owner who has three children, only one of whom is involved in the family-owned company. That child may get the whole business, but if the estate isn’t worth three times the business’ worth, then the distribution of assets isn’t necessarily equal, even though it might be fair.

To address those concerns, the attorneys said they can point their clients toward other tools, such as a life insurance policy, that can help make up the difference. But “no child has a right to an inheritance,” Retzner said.

“By virtue of the fact that you share DNA does not mean you get anything at all, much less equally,” he said.

Case study: farmers

Issues of fairness and equality are prevalent in family-owned farms, Folz said. He also preaches the maxim that fairness is not equality, and he uses the unique aspects of farm succession planning to help his clients work through those issues.

Generally, a family farm has two business entities, Folz, of Dobbs Legal Group, said: the machinery and operations, and the land. A farmer with multiple children might leave the operations to one child who wants to carry on the business, but might divide the land among all the children.

Agriculture also has legal and regulatory facets that are unique to the industry, Folz said. For example, farmers have the option of creating business plans through the United States Department of Agriculture, so Folz has to be mindful that the succession plans he helps his clients create don’t interfere with their federal programs.

Taxes are also a unique issue in agriculture, as farmers can often defer income tax payments that result in very large tax bills that have to be addressed in the future.

There’s also the emotional aspect of being a farmer, which the attorneys say is present in all aspects of estate planning. Farmers have often worked their land for generations, and they struggle with the concept of letting it go or selling it to someone outside the family.

Being proactive

Those emotional considerations are part of why estate planning attorneys stress the importance of proactively developing succession plans. Tensions can ensue among family members even when a plan has been drafted, the attorneys say, and those tensions are only heightened when family members and business associates start from scratch.

In situations where a succession plan is not in place when the owner dies, the attorneys say their goal is to help clients quickly find the next steps that will allow a business to remain operational and valuable. Often, that process involves multiple lawyers and advisers from multiple industries.

“It’s difficult when you no longer have the owner’s input at that time,” Leitch said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.