Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now

Women have been breaking the metaphorical glass ceiling for centuries.

That includes Indiana women in law, who since the nineteenth century have been paving the way for those who’ve come after them.

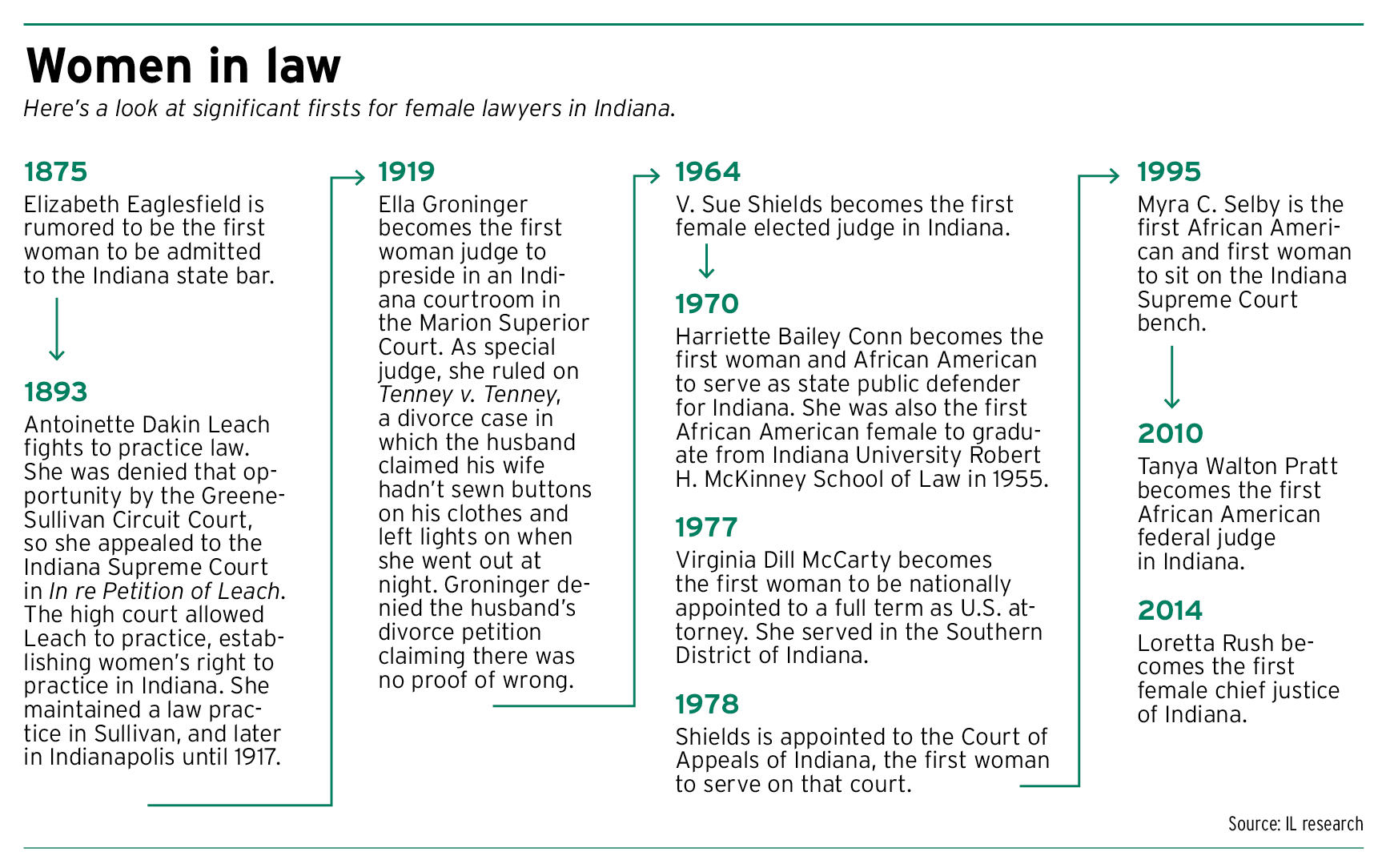

The journey of women in Hoosier law began in 1875, when Elizabeth Eaglesfield is rumored to have become the first woman to be admitted to the Indiana state bar. While there isn’t much proof of how or if she practiced in Indiana, she did later receive her law degree from the University of Michigan.

Amy Vedra, director of reference services at the Indiana Historical Society, hypothesized that Eaglesfield may have found a way to be admitted to the bar without people figuring out she was actually a woman. At the time, bar admission was done on a circuit court basis, rather than one admission for the whole state.

That was the case with Antoinette Dakin Leach, who in 1893 was denied admission to the bar by the Greene-Sullivan Circuit Court.

Leach decided to take her case to the Indiana Supreme Court, which in In re Petition of Leach allowed her to practice. That 1893 decision set off a string of “firsts” for women in Hoosier law that is continuing today.

Gaining traction

While women were given admission to the Indiana bar after Leach, there were still many “firsts” ahead.

The next significant first would come in 1919, when Ella Groninger became the first woman judge to preside in an Indiana courtroom in the Marion County Superior Court.

According to the Indiana Historical Bureau of the Indiana State Library, Groninger acted as special judge in Tenney v. Tenney, a divorce case.

In Tenney, the husband was filing for divorce on the grounds that his wife hadn’t sewn buttons on his clothes and had left lights on when she went out at night. Groninger denied the petition, ruling there was no proof of wrong.

According to the Indiana History Blog, when Groninger was asked about her ruling, she remarked, “The double standard of morality should not be given a chance to grow out of our divorce courts.”

Several decades later in 1977, Virginia Dill McCarty became the first woman to be federally appointed to a full term as U.S. attorney. She was appointed to serve in the Southern District of Indiana.

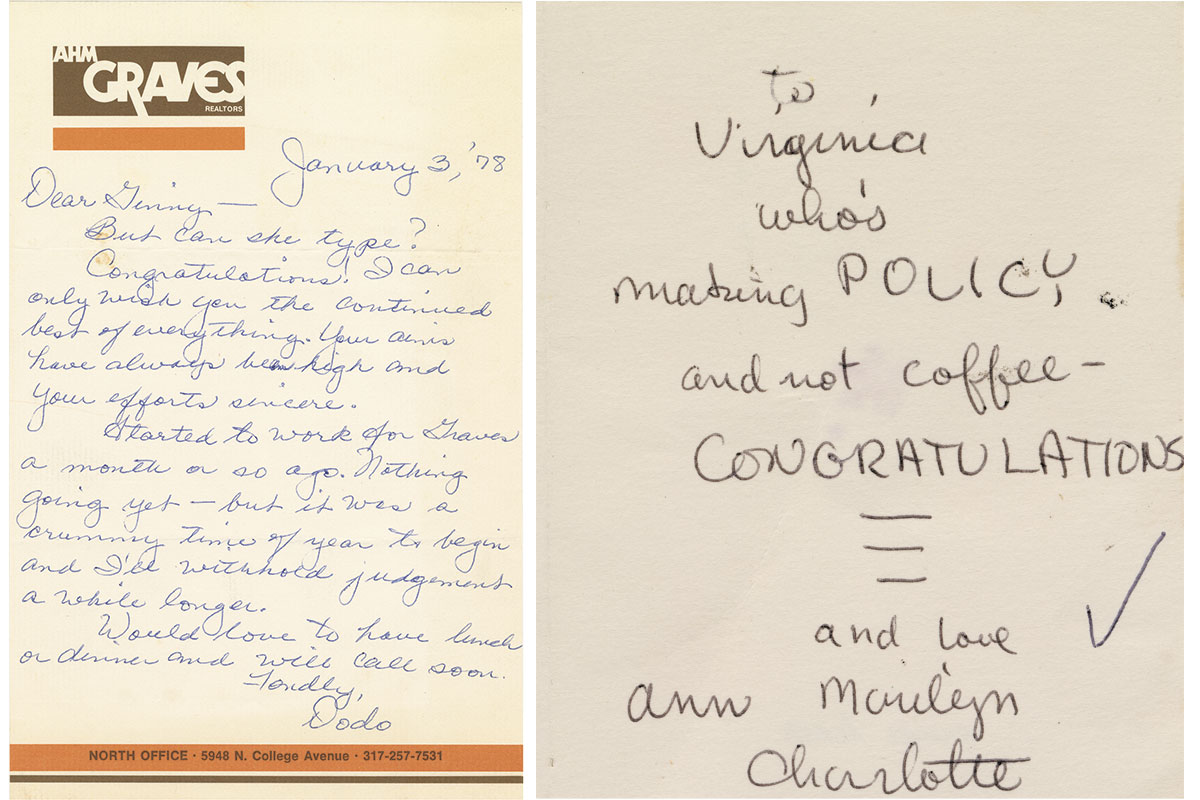

Following that news, McCarty received notes of congratulations saying, “To Virginia, who’s making POLICY and not coffee,” and, “Dear Ginny, But can she type?”

“It was so common for women to move into the field or to be in the field as executive assistants or, as they would have called them then, secretaries, and somebody who was just taking the notes or making the coffee,” Vedra said.

Diverse firsts

Progress for women of color in Hoosier law took longer to make.

It wasn’t until 1955 that Harriette Bailey Conn became the first African American woman to graduate from what is now the Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law. Conn later became the first woman and the first African American to serve as state public defender for Indiana in 1970.

“Just fairness requires that we do get these firsts in the legal profession,” Tanya Walton Pratt, chief judge of the Indiana Southern District Court, said. “It requires diversity in our federal and state courts — not just diversity of color, but all aspects of diversity.”

Pratt herself is considered a historic woman.

In 2010, she became the first African American — and the first Black woman — to serve as judge of any Indiana federal court.

“I would have been happy to have served the rest of my career as a judge in the probate division,” Pratt said.

She had been serving as a probate judge in Marion County when she saw an article on the front page of The Indianapolis Star about Judge David Hamilton joining the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals. His elevation to the federal appeals court meant there was a chance for the first African American judge to join the Indiana Southern District bench as his successor — a role she would come to fill.

Fast forward to 2021, when Pratt would mark another “first”: becoming the first person of color to serve as chief judge of the Indiana Southern District Court.

“The significance of being the first is that it encourages others to reach for the height of our profession,” she said. “I’m just happy that I’ve had the opportunity to be the first and hope that make people proud.”

State court firsts

At the state court level, Indiana Chief Justice Loretta Rush observed that among the dozens of portraits of past and present justices hanging in the Indiana Supreme Court courtroom, only two are of women: herself and Myra Selby.

Selby made Indiana history in 1995 when she was the first African American and the first woman to be appointed to Indiana’s high court. She would go on to serve on the Supreme Court bench until 1999 before returning to practice as a commercial mediator and arbitrator with Ice Miller LLP.

Rush joined the bench in 2012, then became a “first” in 2014 when she was appointed the state’s first female chief justice.

Today, when Rush sees children or school tours at the Indiana Statehouse, she will ask them to look around the Supreme Court chamber.

“I say, ‘Once you look around, what do you notice?’ And they’ll say, ‘Looks like a lot of mad men,’” Rush said. “I’m still the only woman on the bench. It’s very important, so we’re working hard to change that.”

Rush recalled a day a few years ago, when a mother had sent her a photo of her daughter dressed in a wig, glasses and a black robe. The little girl had chosen to dress as the chief justice for a history day celebration at school.

“I have the saying: You have to see the robe to be the robe,” Rush said. “Girls need to see people like you in these roles to think that they can do that as well. And I think that’s for all kinds of diversity.”

Even today, historical “firsts” for women in Hoosier law are being made.

The most recent first came in December, when Judge Dana Kenworthy’s appointment to the Court of Appeals of Indiana gave the court eight female and seven male judges — the first time in the COA’s history that there is a female judge majority on the bench.

Continuing the work

Rush has another saying about female firsts: “Work hard to make sure you’re not the only woman in the room or at the table.”

To that end, the chief advocated for mentoring young women and being there to show it is possible to be in those roles.

Indiana State Bar Association President Amy Dudas agreed that mentoring young women plays a role in making sure firsts are not lasts.

Dudas also said men should be part of the conversation.

“I always bring my husband and my dad (to women’s events) because it’s important that we see men supporting women’s causes as well and recognizing how important that is,” Dudas said.

In her own life, Rush recalled receiving pushback when she was looking for a job in the law — even though she was a top student in law school.

“I think that you’ve got to take some risks,” Rush said. “You can’t be afraid of the word ‘no.’ You’ve got to push.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.