Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIsolation, economic anxiety and fear of the coronavirus were dangerous fruits of the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly for individuals struggling with a substance use disorder, experts say. Bundled together, those factors made for a devastating year of increased drug overdose deaths that reached an all-time nationwide high.

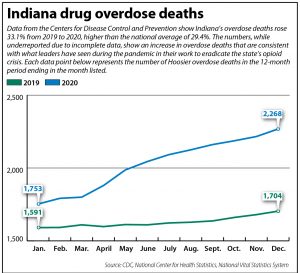

In 2020, the number of Americans who overdosed spiked nearly 30% to more than 92,000, according to provisional numbers from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released in July.

The same report found that Indiana saw a 33.1% increase in drug overdoses for the 12-month period ending December 2020.

The Hoosier State also experienced a 67% increase in the administration of naloxone and a 50% increase in overdoses at emergency departments statewide in 2020 over 2019, according to Doug Huntsinger, executive director of drug prevention, treatment and enforcement in the Indiana Governor’s Office.

Already in 2021, the state has seen a 26% increase in naloxone administration and a 20% increase in overdoses at emergency departments, the state drug czar said.

“We are still seeing large numbers,” Huntsinger said. “As we’ve moved into 2021, I really don’t think we’ve hit our peak yet. And obviously, the overdose death numbers begin to tell that story.”

‘Fragile states of recovery’

Indiana’s judicial branch in 2017 pledged to help fight the opioid epidemic, led by Indiana Chief Justice Loretta Rush. Despite those efforts, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Hoosier communities combatting the drug crisis has been felt in every corner of state.

Brandon George, executive director of the Indiana Addictions Issues Coalition, said the community of supporters and recovery organizations working to eradicate the state’s drug crisis anticipated a 20% increase in overdoses last year. What they saw was much higher.

“But the big kicker is that we have not plateaued,” George added. “The numbers are still climbing dramatically.”

Indeed, while on the bench, Warren Circuit Judge Hunter Reece said he frequently sees substance abuse among criminal, juvenile and child in need of services cases. Reece presides over the Bi-County Accountability Court, a problem-solving drug court run out of the Fountain and Warren Circuit Courts.

As a result of the pandemic, Reece said he has seen firsthand an increase in drug use relapses and a decline in the stability of cases.

“In homes we saw a 38% increase in CHINS cases in our county (in 2020), and substantially all of those have some tie to substance abuse from one or both parents. We also saw people with years of sobriety relapse during COVID-19 that were near graduation” from drug court, he said.

Reece said he also saw a rise in the number of petitions to revoke probation stemming from relapses. The trial court judge attributed that to a decline in treatment providers during the early stages of the pandemic, particularly in rural areas unaccustomed to providing — or receiving — virtual treatment.

“Many in our rural communities lack stable internet or don’t have the bandwidth to allow for virtual streaming,” Reece explained.

George agreed that while efforts to utilize telehealth during the pandemic were promising for some communities, it only widened the disparity between Hoosiers who can access such services and those who cannot.

Also, reduced supervision by probation officers who were working on limited schedules from home, as well as scaled back or stayed drug court proceedings, were additional factors that contributed to the relapses Reece saw, the judge said. Many participants became reclusive without in-person encouragement, he said.

“They were stuck at home, they were depressed, they weren’t working, many were seeing financial problems and hearing on the news a lot of stress and drama about COVID,” Reece said. “A lot of these people were in fragile states of recovery anyway, so that’s where we saw relapses start happening.”

A black hole

A black hole

A $26 billion multistate settlement deal was struck last month with opioid distributors as part of the ongoing effort to address the nationwide opioid addiction and overdose crisis. Indiana is set to receive $507 million from that settlement, according to Indiana Attorney General Todd Rokita.

Drug distributors have taken heavy blows for the role they’ve played in exacerbating the crisis — as they should, George said. Conversely, he said, of the roughly 100 people he sees with addictions each day, only one might stem from an opioid prescription from their doctor.

“That story is not completely an urban myth. I just think it’s really important to not push on that narrative anymore, because it’s just not accurate,” he opined.

Hopelessness and despair coupled with a volatile drug supply are the two major contributors to the country’s substance abuse crisis, George said, adding that “COVID-19 exacerbated it an enormous amount.”

“We’re living in that space right now,” he said. “We are in an overdose crisis. It’s not an opioid crisis or epidemic at this point anymore.”

In an effort to bring more hope to Indiana, Stephanie Anderson is leading the charge at the recently opened Recovery Centers of America at Indianapolis, serving as CEO. The treatment center opened in the fall of 2020 and offers inpatient and outpatient services to the greater Indiana region.

“We know there are lives to be saved here,” Anderson said. “In the past people who wanted this level of treatment in this type of facility had to go out of state. We want Hoosiers to have space like that to recover in Indiana.”

But with only 40 of the treatment center’s 112 beds currently occupied, Anderson said her team has noticed a concerning trend: People aren’t asking for help. Instead, she said, many are afraid of taking a noticeable amount of time off work while they participate in a one-week or one-month treatment program. Prior to COVID-19, those concerns weren’t as prevalent, she said.

“People are using more, drinking more and they are flying under the radar more often. Most people start to get noticed by their coworkers, peers or friends. But with the social isolation and the quarantine, people don’t have that opportunity to have others put their eyes on them and say, ‘I don’t think you’re OK,’” she said.

Also, unhealthy coping skills were flamed from a flicker to a bonfire during the pandemic, Anderson said, widening the black hole that Hoosiers with substance use disorders teetering on the edge are falling into.

But despite the sometimes bleak outlook, Anderson said she expects more patients will check into treatment soon.

“I really anticipate that we haven’t seen the end of it yet,” she said. “The number will most likely continue to rise for some time as we flux in and out of the pandemic status. I think we will probably continue to be challenged for several years.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.