Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowA new report from a national sentencing reform nonprofit is highlighting continued concerns about youth offenders housed in adult facilities, rather than juvenile centers.

The December report from The Sentencing Project offers a simple theme: Housing youth in adult facilities does little to curb delinquent behavior.

“When you put a young person in a prison, you don’t really connect them with services that address their underlying offenses. It’s really just a place to waste time until it’s time to go home,” Josh Rovner, director of youth justice at The Sentencing Project, said. “For many of these kids, there’s no shortage of issues in their lives — starting with poverty and lack of opportunity and lousy schools — that may have led them to offending, and prison doesn’t solve any of those things.”

The solution to juvenile delinquency, Rovner added, can start with the why behind the offense, rather than the what.

“I think the juvenile system is much more equipped to deal with those problems than the adult system is,” he said. “I also think that we can’t expect law enforcement to solve those problems of lack of opportunity or poverty or fear. That’s not what we should expect law enforcement to do or expect our courts to do. But we can invest in robust social services, mental health care in schools and access to counseling, including counseling that brings in the family.”

Multiple factors

Multiple factors

Indiana is one of 44 states that house some juvenile offenders with adults. But under the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act — established in 1974 and reauthorized in 2018 — juveniles charged with adult crimes cannot be held in adult jails pretrial unless it is in the “interest of justice.”

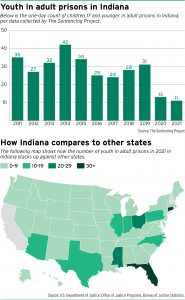

In 2021, 11 juveniles were housed in prisons with adults, according to the Indiana Department of Correction’s one-day count, provided by The Sentencing Project. The one-day count is the count from the last day of the year, meaning it doesn’t include an offender who was incarcerated for most the year but was released before the one-day count occurred.

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Indiana ranks ninth nationally for the number of youth in adult facilities. Under Indiana Code § 31-30-1-4, juvenile offenses that can be waived into adult court once a child turns 16 involve handguns, rape, attempted murder, murder, kidnapping and certain robbery offenses.

Elkhart County Prosecutor Vicki Becker pointed to troubles at home as a common cause of serious juvenile offenses.

“Generally speaking, when they have a strong family unit, they’re not usually the kids that are committing delinquent, and certainly not violent, acts,” Becker said.

Issues such as abandonment, drug addiction or mental illness can prompt Department of Child Services intervention, Becker noted. In those cases, the parties may look for alternatives to detention if the juvenile has committed a crime.

Several factors are considered before a juvenile is waived into adult court and, relatedly, an adult detention facility. The Juvenile Justice Delinquency and Prevention Act, for example, considers physical and mental maturity, risk to self or others, and any prior involvement with the criminal justice system.

“This is the kind of thing that a child would absolutely not be permitted in that (adult) facility until this finding was made,” Becker said.

Some Indiana counties do not have a juvenile detention center. Thus, if a child is housed in a juvenile facility rather than an adult facility, they can end up hundreds of miles from home.

“Usually what happens is (counties) have a contract with a regional or a neighboring area that has a facility that allows them to place their juveniles there,” Becker said. “I have heard of places in the less populous areas of southern Indiana that they have to drive 90 to 100 miles to get to a facility where a juvenile can be detained.”

Legislative efforts

JauNae Hanger, president of the Children’s Policy and Law Initiative of Indiana, said her organization is keeping an eye on multiple bills this legislative session.

First is House Bill 1481, which would provide that juvenile delinquency law does not apply to a child younger than 10, or to a child who is 10 or 11 unless the alleged offense is murder. Thus, aside from murder cases, a child would have to be 12 years old to face a delinquency allegation.

“Right now there’s no minimum age for juvenile court jurisdiction, so you actually see very young children being tried in juvenile court under the age of 12,” Hanger said. “I think we have a lot of conversation around what is age and developmentally appropriate for very young children who are charged with serious offenses.”

HB 1481, authored by Rep. Robin Shackleford, D-Indianapolis, has been assigned to the House Courts and Criminal Code Committee but hadn’t been scheduled for a hearing at Indiana Lawyer deadline.

Another bill Hanger is following is Senate Bill 410. That bill, authored by GOP Sen. Sue Glick of LaGrange, a former prosecutor, would institute a slew of juvenile justice reforms.

Among the reforms included in SB 410 is changing the age range in which a person can be made a ward of the Department of Correction from 13-22 at the time a dispositional decree is entered, with an exception for murder.

“There’s a lot of potential there for some significant reform,” Hanger said.

That bill has been assigned to the Senate Corrections and Criminal Law Committee but had not been scheduled for a hearing at IL deadline.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.